The tiger is the largest living cat species that is among the most recognisable and popular of the world’s charismatic megafauna. Unlike the tiger that inhabits the jungles, there is an equally majestic tiger that bejewels the waters. It is a large, wondrous fish that gleams gold as it glides through dappled streams and rivers. For the uninitiated, that’s Mahseer, the tiger of the freshwater.

Once upon a time, the freshwater species happily thrived in the rapids of the Himalayan and Sahyadri ranges, besides other rivers and lakes across the country. Soon, the mighty Mahseer fell prey to the greed of man and became the target of fishermen and fishing companies. Of the 15 species of Mahseer in India, five faced the dire threat of extinction.

It was exactly 50 years ago when Tata Power decided to step in to save the grand fish that was literally feeling out of water. Its efforts paid off and this year on World Environment Day, the company announced that the Blue-Finned (Tor Khudree) — one of the two Mahseer species being bred at Tata Power’s Walvan Hatchery in Lonavala — is now off the IUCN red list. The IUCN has granted it the status of ‘Least Concern’, meaning the species is no longer in danger of being extinct.

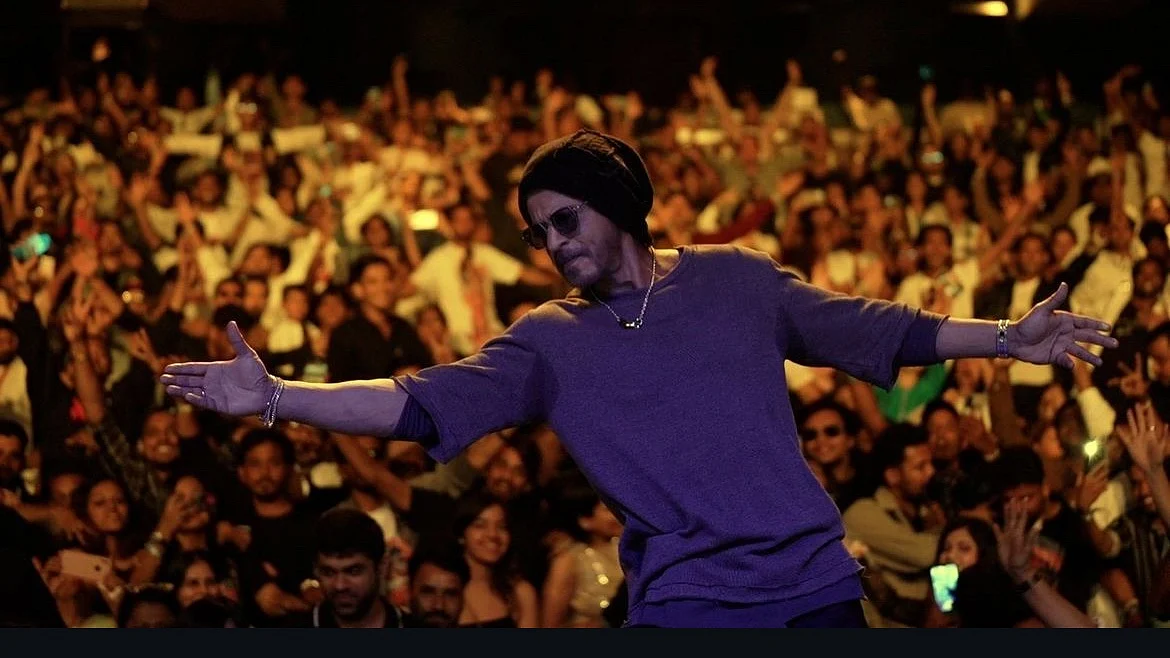

pics: Tata Power

The Golden Mahseer is still on the list, which calls for a greater commitment to helping the endangered species swim out of the red. “The initiative that Tata Power started 50 years ago, now has an urgency to succeed like never before. If nothing else, we owe it to our children. And this could only show up by keeping crucial species just like the Mahseer alive,” says Vivek Vishwasrao, Head — Biodiversity, Tata Power.

Mahseer and ecological balance

Rushikesh Chavan, Head — The Habitats Trust, couldn’t agree more with Vishwasrao on Maheseer’s importancy for riparian ecology. “Mahseer is equated with the tiger. Its name comes from mahi means fish and sher from tiger. There are about 15 species of Mahseer in India some classified as endangered. They are omnivores and eat a variety of food, making them an indicator of river ecology and water security,” he says.

River ecologist and conservationist from Bengaluru Neethi Mahesh, who is currently engaged with WCS-India, has been relentlessly working in spatial ecology and conservation of Mahseer fish with the Jenu Kuruba, a forest-dwelling tribe in the Western Ghats for which she also received The Habitats Trust’s ‘Conservation Hero Grant’ in 2019.

Mahesh, who is working on a project titled, Riparian Habitat Conservation along the Cauvery river in Coorg district, says, “Mahseer are large-bodied fish, belonging to the family Cyprinidae or carps, as they are commonly referred to. Mahseer are considered indicator species of freshwater streams and rivers, which means that any habitat altering influences, especially through anthropogenic stressors, can affect the survival of the species.”

She highlights how Mahseer’s omnivorous nature makes it hard to ignore the possible role in seed dispersal of important species of riparian flora. “They are also prey to predatory species such as otters, crocodiles and piscivorous birds, thus playing an important role in the food chain,” says Mahesh.

Highlighting the need to increase the number of Mahseer to stabilise the bio-diversity while keeping river pollution under check, Vishwasrao says, “Mahseer is sensitive to dissolved oxygen levels, water temperature and sudden climatic modifications. Apart from this, it does not have the capacity to bear pollution at all. So, whilst we spew wastes into our rivers, we aren’t only sounding a death knell for the Mahseer, but are also dropping an essential indicator of freshwater ecosystems.”

Conservation measures

Mahesh explains how there have been several recommendations and attempts to promote Mahseer as a ‘Flagship species’ (a charismatic animal that promotes awareness), similar to the recognition of tigers as flagship species. “While tiger conservation is receiving attention at the landscape level, Mahseer conservation can bring the same level of importance to riverscapes,” she says.

But Mahseer conservation, although in need of attention is not something new in India’s cultural-religious context. Revered in various forms, including as an incarnation of Lord Vishnu, Mahseer fish have been protected since time immemorial in many temples, along the rivers in India.

“Community fish sanctuaries, are more common in the North-East; for instance, Meghalaya is known for its exemplary management and protection of fish populations, passed down from indigenous knowledge and generations of sustainable management of natural/ fishery resources. Conservation NGOs and eco-tourism-based recreational angling groups, also play a vital role in the conservation of Mahseer, with further scope for recognition,” she adds.

Chavan explains how conservation efforts are still a mixed bag. “There are good conservation initiatives that are bringing Mahseer back from extinction but overall it is a worry. The inherent biology of Mahseer (long maturity, low fecundity, and long hatching period) along with habitat destruction, overfishing, and pollution make it difficult for the species,” he says.

Vishwasrao highlights the importance of learning the freshwater ecology to understand the role of Mahseer conservation, seeks concerted efforts at the individual and organisational level to reduce water pollution and calls for community support and volunteering by the organisations and NGOs for visible results in this direction.

Applauding the efforts taken by Tata Power, Chavan says, “Tata has set an example of what industry can do. Academic institutions need to do more ecological work on the hydrology of streams that Mahseer occupy. The list is long, so pick the best way to contribute.”

Catching them young

According to Vishwasrao, measures for Mahseer conservation could include more natural breeding grounds, changes in fishing practices and encouraging community participation to sustain this project for a long time. “Since its inception, Tata Power’s Mahseer initiative has been conducting various activities for youngsters under their Club Enerji initiative. These include excursions that raise awareness about the gorgeous Mahseer. The idea is to encourage children to learn about an important aspect of their ecology, while also initiating the slightly older kids into enjoying the sport of fishing the Mahseer, and then letting it back into the water,” says Vishwasrao.

These activities bode well for Mahseer. Mahesh attributes the growing awareness towards Mahseer, outside of regions they are found in, to coverage in the media, and efforts of groups and individuals working towards conservation of the species. “The tiger of the freshwater is also more recognised as a hot topic for research, conservation and community outreach. One of the recent initiatives included an organisation collaborating with a group of artists to create a Mahseer installation made out of recycled material, with a walk-through gallery filled with Mahseer, freshwater fish, habitat images and information inside the model. It got people from all walks of life to take an interest in freshwater fish and rivers, which receive little to no attention,” she says.

Stressing on the need for intensive and concerted efforts for the conservation of Mahseer as these are widely distributed and though there are general threats, Chavan adds, “However, localised threats need to be identified and specific conservation programmes need to be implemented.”

Mahesh urges civil society groups and NGOs to be more vocal about sustainable land use along rivers to ensure pollution and activities that disturb the ecosystem are curbed, giving rivers and their fish populations a better chance for survival. “Mahseer conservation requires a state/ river-wise plan, with the demarcation of important Mahseer habitats to focus on. What we need is funding not just for Mahseer, but a holistic approach towards Mahseer conservation which includes the entire river habitat. Organisations and institutions need to support more individuals in the field to carry out research, outreach and conservation interventions, such as outreach and restoration where required,” says the river ecologist.

Tourism prospects

Tata Power that has been involved in the field of breeding Mahseer for 50 years and counting is elated at the outcome of its untiring efforts. “Unlike typical corporate practice, success in this venture is measured by literally going into the red, so that the Mahseer goes off the IUCN endangered list! Rivers and lakes that were once bereft of the Mahseer are now teeming with them after hatchlings introduced from the Walvan hatchery have started breeding and increasing. Mahseer are also now being increasingly sighted at various points by avid anglers,” says Vishwasrao.

Mahesh sees a great deal of potential for Mahseer tourism in the country. “We already have fish sanctuaries, where tourists and religious devotees visit. The untapped potential lies with the eco-tourism industry, with catch and release (C&R) recreational angling. Sustainable means of C&R angling tourism have been proven as a great source of revenue generation for local communities, while monitoring and protecting fish populations, through strictly enforced guidelines and rules,” she adds.

However, Chavan agrees that there is, but one must be careful. “Tourism is a double-edged sword. Poorly designed and implemented tourism models can ruin not just Mahseer but also disturb, if not destroy, river ecology and water security,” he says.