A fresh crisis is brewing in the Indian milk industry. The causes are two – the current lockdown conditions, and a milk surplus.

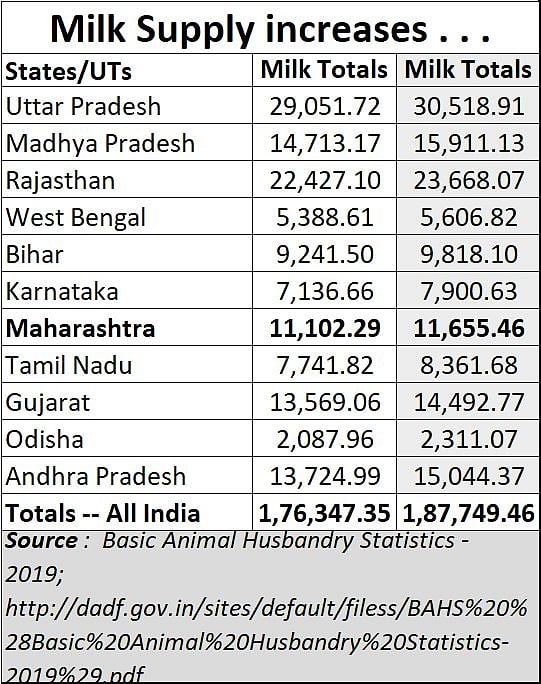

First, there is no denying that milk production has increased. (see chart 1)

Chart 1 |

But the current lockdown conditions have caused a slump in demand. Many people cannot go to shops to get milk. Its availability has got limited to a few outlets. Restaurants are closed, and only carry home services are offered by many restaurants. As a result, the consumption of tea, coffee, curd, buttermilk and lassi (among other milk products) has also declined.

Added to this is the fact that India’s milk production has been rising raster than demand. Demand could have been stoked, but lockdown conditions prevent this.

Consequently, many private milk producer-farmers – who are nor part of any good milk cooperative – complain that the milk they produce is now collected every alternate day, or is being collected at distress prices at times even lower than Rs.14 a litre (good cooperatives offer around Rs.26-28 per litre for cow’s milk and upwards of Rs.30 for buffalo’s milk). The distress they face is tremendous.

It is not surprising, therefore that these farmers are coming out on to roads and pouring their milk there as a mark of protest. They need a bailout.

One answer was to allow the cooperative movement to spread. This is what happened in Maharashtra, for instance, when the Fadnavis government found the sugarcane-linked milk cooperatives not giving farmers the right price for the milk they produce. The government then requested NDDB to set up a cooperative in Nagpur and significantly large milk processing capacity. The most important stage in all processing plants is their ability to convert surplus milk into milk powder (SMP) and then use the same powder when milk supply becomes lean, and reconstitute it into milk again. The rest of the milk is converted into milk products like buttermilk, lassi, curd or cheese.

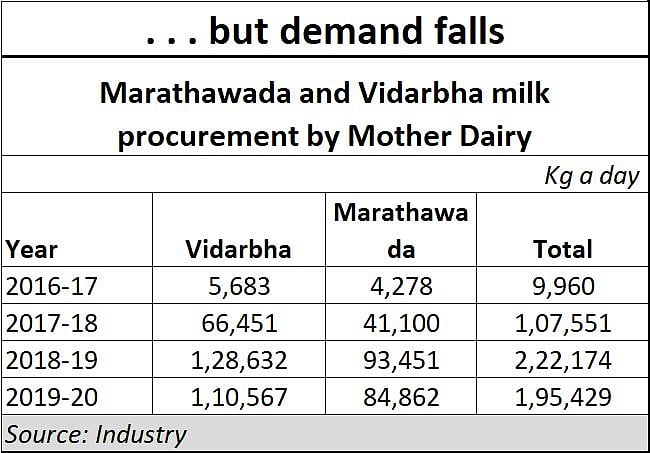

Unfortunately, political compulsions probably caused Maharashtra to go slow on milk procurement in Vidarbha and Marathawada as the table alongside suggests. Thus, while milk procurement increased till 2018-19, it slumped in 2019-20.

Reducing procurement when milk supply has grown is unusual. Probably, someone wanted the sugar-milk cooperatives to benefit by procuring milk at lower prices. Either way, the farmers were unhappy

Unless good cooperatives proliferate, farmers will remain exploited. The other alternative is to encourage responsible private sector players like Hatsun and Nestle which offer farmers more money that private procurement agencies, or even milk cooperatives run by politicians in Maharashtra. Hatsun is, today, the largest private player in the country, and has grown without any subsidy from any government (just like GCMMF). As pointed out earlier, Verghese Kurien, the father of the milk revolution in India, was convinced (rightly) that the road to perdition for farmers was to wean them on subsidies.

Unfortunately, little data is available on the quantity of milk going for distress sale each day. But every industry expert admits that the nationwide lockdown measures to contain the spread of COVID-19 pandemic has severely impacted the dairy sector as well. Disruptions in milk procurement, processing and marketing have been reported by almost all dairy cooperatives.

According to the latest data compiled from the Dairy Cooperatives across India, liquid milk sale by the Dairy Cooperatives during the lockdown period at the national level declined by about 20% and among the major dairying States. What has happened is that surplus milk conditions were bad enough. The lockdown made it worse.

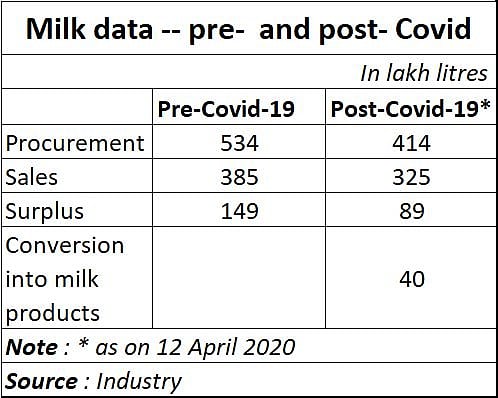

Just study the numbers. Milk cooperatives and (NDDB approved) producer companies collectively procured 534 lakh litres of milk per day during pre-Covid times. Post-Covid, on account of transportation and logistical bottlenecks, this procurement dropped to 515 lakh litres as on 12 April 2020. Against this Pre-Covid sales were 385 lakh litres of milk a day while post-Covid sales dropped to 325 lakh litres.

Covid lockdowns had led to a drop in demand, hence the surplus milk capacity even with cooperatives and producer companies. During the lockdown period, almost 40 lakh litres of surplus milk per day are being converted into commodities (including SMP). Post lockdown, this surplus is expected to drop to 20 lakh litres a day. It is worth bearing in mind that these numbers do not include milk from private milk producer-farmers. Add that, and the magnitude of the problem is understandable.

Fortunately, the Central government has woken up to this. Based on NDDB’s suggestion, the government has already approved a scheme to provide working capital support to cooperative and producer owned institutions. Maybe, it is time the central government and state governments also use the surplus milk to offer free of cost to labour camps and isolation wards. This will ease the pressure on milk stocks, reduce the surplus milk, and ensure that marginalised, homeless and jobless people can benefit from milk consumption during these days and months of acute distress. The scheme can also be extended to people living in slums and migrant labour camps.

It will go a long way in aiding the milk industry without subsidies to a few favoured people. As mentioned earlier subsidies can destroy the milk industry. Allowing for offtake of milk from cooperatives and producer companies for social welfare could be the first step towards creating a safety net at least for daily nutritional needs during these turbulent times.

Finally, all state governments should work harder to bring all private milk producers under the ambit of milk cooperatives and NDDB approved producer companies. Else they should promote good and responsible private sector companies like Hatsun. This way, the milk producer-farmers can become part of a larger market, get a safety net of procurement prices for the milk they produce and ensure a steady income stream for themselves even when crop pricing and procurement fails.

It is worth recalling, that milk under good cooperatives and private managements has helped farmers climb the prosperity ladder5 faster than any other agriculture-related scheme of the government. That this has been done without subsidies is thanks to the legacy of the late Dr. Verghese Kurien.

The author is consulting editor with FPJ