26 November 2021 is the date on which much of India will be celebrating the 100th birth anniversary of Verghese Kurien, the Milk Man of India. He transformed India as dramatically as The Tatas and the Birlas did to the industrial landscape in this country. Just as India would be woefully handicapped without the contributions of people like the Tatas and the Birlas, this country would have been abjectly poorer had it not been for Kurien.

He had several beliefs -- which he implemented, unlike most politicians. He had a strategic vision for India. It needs constant reiteration today.

Strategic vision

He believed that where agriculture was concerned, the farmer was the most important part of the entire food cycle. Without the farmer there would be no role for the processor, market maker and the distributor. Hence, he should get the highest share of the market price of milk. This was blasphemy to milk processing companies. Worldwide, the farmer got only one-third of the market price, the processor got another third, and the rest went for marketing and distribution.

Kurien began with the premise that the farmer should get at least 50% of the market price of his produce. When global processing and marketing companies refused to accept his formula, and help him out, he set up his own processing facilities. To ensure that processing machines were available at reasonable costs for Indian produce, he set up a separate division for making dairy equipment. He did that with cattle feed, artificial insemination centres, cattle vaccines, and the entire gamut of services a dairy industry required. Today, each of these activities is profitable and a market leader.

He also firmly believed that in India, agriculture, especially the dairy sector, would have to be based on production by the masses, not mass production.

To make all the above beliefs turn into reality, he needed a market making entity, which Lal Bahadur Shastri, the then prime minister of India, agreed to let him set up. That was NDDB or the National Dairy Dev elopement Board. Its primary function was to promote the formation of milk cooperatives. Its corollary function was to protect milk prices for farmers, and to make vibrant the market for milk. It did so by first exhorting the government to channel all milk and milk product imports (even gifts and aid) through the NDDB. This would then be released in the market at market rates, thus ensuring that the market price of milk for farmers was not adversely impacted. The surplus from the procurement price and sales were used by NDDB to promote the dairy sector. It was a brilliant strategy to ensure that the dairy sector did not depend on government support or doles. Moreover, since the development fund was not a government subsidy, it did not violate any World Trade Organisation norms.

Subsidies, for Kurien was a bad word. It rewarded the inefficient, and crippled the efficient. It made beggars out of proud farmers who could stand on their own feet. Politicians did not like this. They still don’t.

Promoting cooperatives

On the milk production side, he promoted milk cooperatives, the largest of which are the ones under the Gujarat Cooperative Milk Marketing Federation (GCMMF). It sells milk and milk products under the Amul brand. Today, Amul is the market leader in India, even Asia, and its farmers get over 80% of the market price of milk. He had turned global market concepts on their head. It was a triumph of the Kurien model – something that the developed world could not fight against.

The price of milk is determined on the fat content of the produce, which is collected twice every day at stipulated collection centres.

Thanks to better progeny (artificial insemination has a big role in this), better cattle feed, and good cattle rearing practices, the milk producing farmer can earn under cooperatives and world class private sector milk producer companies like Hatsun a profit of at least Rs.100 per cattle per day for 300 days a year. The farmer gets this money every day (in some places he gets it once a week) directly into his account. No agricultural produce allows guaranteed cash inflows to the farmer on a daily/weekly basis, as does milk.

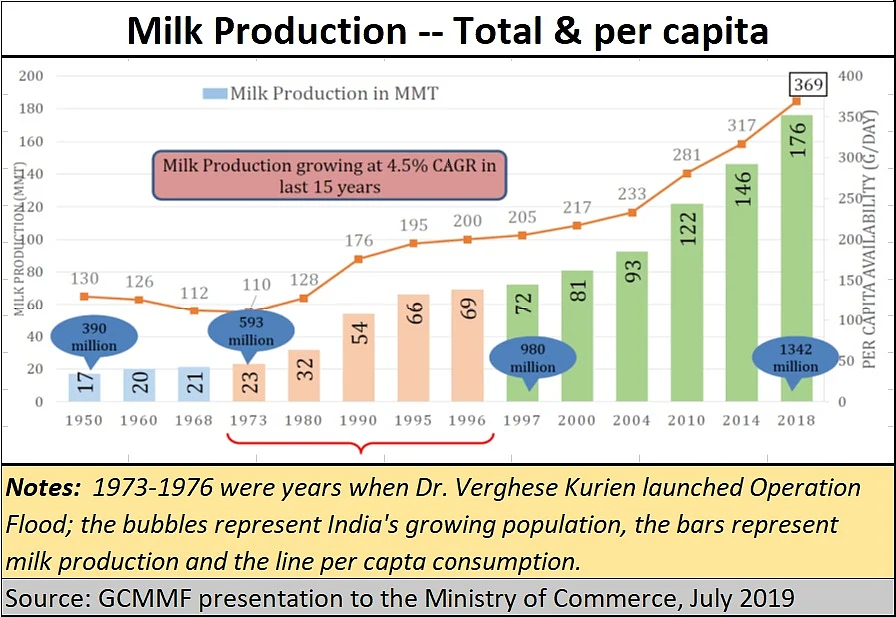

What NDDB does, often in consultation with GCMMF and other major milk producers, is to ensure that the price of milk goes up steadily, year after year in very small doses. Thus, the customer does not feel the pinch of higher milk process. Thus, milk prices do not fluctuate as wildly as those for other crops. The farmer is assured of a price support mechanism, and India has emerged as the global leader in milk production.

Kurien knew that India was destined to be a global leader – it enjoyed strategic advantages that no other country enjoys. He knew that India would remain the world’s lowest cost milk producer as well. And he ensured that in all cases, the farmer remained the focus of the entire milk market picture.

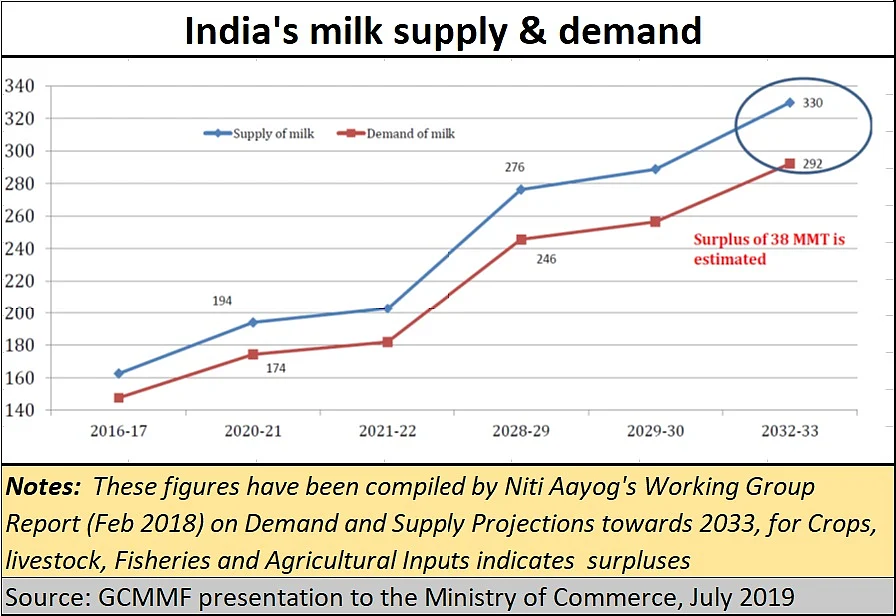

Today the dairy sector feeds some 10 crore families (or 50 crore people). It is a sector which self-employs the largest number of people. It accounts for a GDP share of around 5% -- that is larger than any other agricultural crop (even larger than rice and wheat combined). It is the backbone of rural prosperity which occupies over 50% of India’s population. It has kept on growing, and so has the demand for milk. Both nourish each other.

Clearly, the stronger the milk sector gets, the greater the chances of rural prosperity. Conversely, the more damage this sector faces, the bigger the loss to the entire nation.

This is a lesson many demagogues forget.

Chipping away at Kurien’s legacy

Policymakers have lately begun to chip away at the independence of farmers (the three farm laws had to be abolished. They were not in farmer interests as this author has said repeatedly.

The government has allowed (limited) import of milk and milk products – not through the NDDB -- something Kurien was dead set against. It almost sold out the Indian dairy sector to New Zealand. Fortunately, a huge groundswell of protest made the politicians backtrack.

They have reintroduced the concept of subsidies for milk, which will only hurt the efficient, and promote the inefficient. This way, the industry is now being politicised. Expecty trouble.

NDDB, the nodal organisation created by Kurien remains without a full-time chairman for almost a year now – two short tenure acting chairpersons have headed it since the retirement of the earlier chairman. That is not a good sign.

In other words, the government has tried to erode the independence of the farmer. One crass politician even dared to remark that Kurien actually wanted to promote Christianity, and had to take back his words and backtrack in the face of public outrage.

On his 100th birth anniversary one hopes better sense guides our policy makers:

That they do not undo the tremendous wealth and dignity Kurien brought to the milk sector and tried to do so with other agricultural produce – especially vegetables and fruits.

That they understand that the Kurien method of creating a large market maker for each agricultural product, independent of government control, is crucial to farm welfare – whether through a farmer producer federation (FPO) or through a body owned by farmers.

That NDDB is allowed to remain the focal body which can steer the policies that are good for the entire farm sector.

That it ensures a minimum purchase price for milk at Rs.26 (depending on fat content), and not exploit and impoverish them as has been done in Uttar Pradesh.

That it protects the interest of consumer, without hurting the interest of farmers. Imports of agricultural products should be only through an organisation like NDDB (FPO Federations are good possibilities) so that the price for the farmer must not get depressed. Already, domestic production of edible oil and mustard has been battered through imports at lower prices.

Kurien’s legacy has helped India realise that it can become the strongest player in the dairy sector. His principles and strategies are relevant to every other agricultural produce as well. That is what the three farm laws were regressive. They would have further politicised agriculture, which is what Kurien was steadfastly against.

The author is consulting editor with FPJ