These columns have constantly written about the desperate need for investments. We wrote about this just last month, It was immediately after Prime minister Narendra Modi addressed global funds -- which have about $6 trillion of assets under management -- to invest in India.

The prime minister tried to assure potential investors that India was a safe, stable, and potentially profitable destination for investments. That may be so.

But there are risks. Almost immediately thereafter there was a lockout declared at Toyota’s Bidadi plant in Karnataka. Lockouts do happen, and one lockout should not be the example to determine the investment hazards in India. But the lockout drew attention to some rather worrying developments on the labour front.

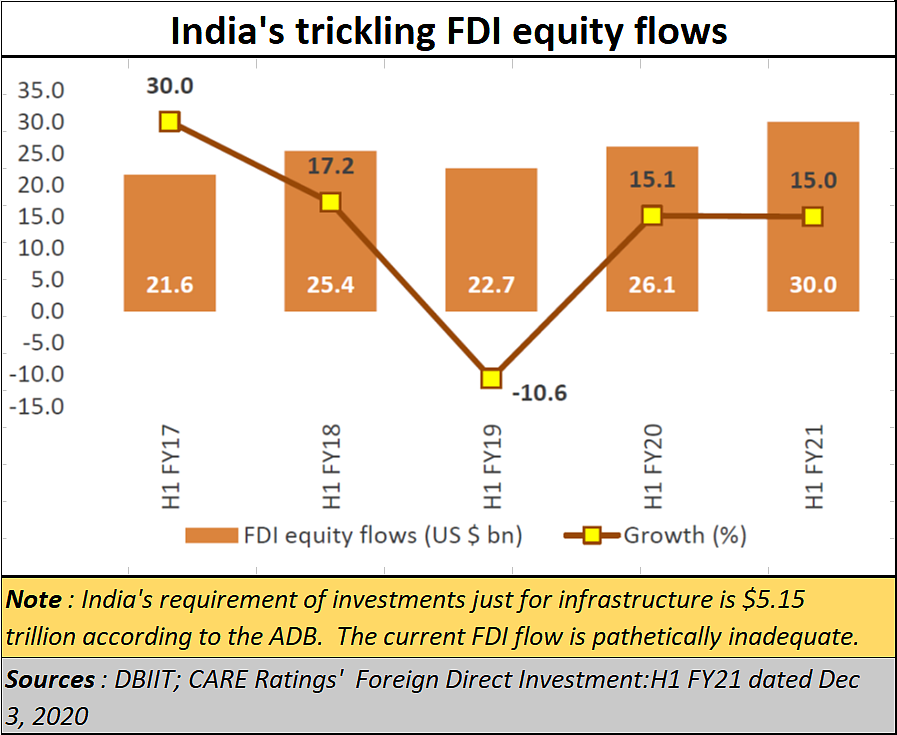

The government, in a move to improve the investment climate, tried to introduce model labour laws. But more than a dozen states refused to implement such laws (labour is a state subject as well). India needs investments quickly. And the $60-80 billion a year won’t be enough. Remember, India need at least $5.15 trillion of investment just for infrastructure by 2030.

Moreover, as Madan Sabnavis, chief economist, CARE Ratings, explains, India wants to be a $5 trillion economy. That comes to around Rs 375 lakh crore of GDP. That would require 30% of this number – or Rs.110 lakh crore -- to be investment on an annual basis. Today, even if $100 billion comes in as FDI, it amounts to just Rs 8 lakh crore — it is a small proportion of Rs 110 lakh crore.

Many other states are trying to introduce new forms of job reservation for locals. And the spectre of reservations for backward classes is a Damocles’ sword that continues to hang over the heads of private sector companies. This is because the government has made job reservation mandatory for government-owned companies and banks. Politicians now believe that such reservations need to be extended to private sector companies as well.

The government hasn’t tried asking them why the absence of reservations is welcomes when forming cricket teams, but not when it comes to jobs or seats in institutes of higher education. India’s politicians fail to realise that compulsory enrolment of all students (backward and non-backward) at the school level is one thing. The Indian constitution mandates the government to provide primary school education. But when it comes to higher education, shouldn’t merit be the sole standard?

To ensure that students from ‘backward’ communities learn as well as those from other communities, it is the responsibility of the government to provide them with additional inputs – including special teachers – to bring them on par with other privileged classes. But when you order reservation of teacher posts, you compromise quality. That affects all students, and the standards of education as well. And the problem that should have bee solved at the school level is allowed to fester even at college levels.

This is the invisible dread that investors see in India. They see politicians beginning to rouse the rabble, demanding reservations in jobs, which then means that companies will not be able to hire the most competent. That is a terrible cost to business productivity. It is a risk that few talk about, or even acknowledge.

That is why it was both amusing and horrifying to hear the Union minister of commerce declaring on 3 December that India’s exports would cross the $ 1 trillion mark by 2025. Do exports take place just at the snap of one’s fingers? Where are the investments required to create jobs? Moreover, how will jobs be productive if companies cannot hire the best? It is such fanciful statements that worries investors even more – it is proof that policy makers cannot come to terms with reality.

True, the minister did say that quality, technology, and scale of production -- not government subsidies -- will help India take its annual exports to $1 trillion. He also exhorted exporters and the industry as a whole to target USD 1 trillion worth of shipments.

That could be a rousing speech, but it cannot come true unless a few things are addressed first.

Most important is the quality of the workforce. That requires quality education. It means advising the courts to haul up politicians seeking to dumb down school and university syllabi and standards on the grounds of making life easier for students – pandemic or not. All these demagogues need is an excuse. Someone commits suicide. Instead of asking for counsellors, they demand that exams be made easier, or the syllabus be diluted.

Instead of allowing students to study anything they want, demagogues want to decide what students should study. Not surprisingly, even the New Education Policy (NEP) opted to ban the study of Chinese (even though it is the place from where most business opportunities will emerge across the world). Someone should have advised the minister that even the US did not ban the study of Russian during the Cold War. Learning an enemy’s language is good for security. And learning the language of the world’s most populous country, and the fastest growing economy, is highly desirable.

Instead of increasing the seats for medical education, the government allows a black market to become bigger, and the clamour for reservations to grow shriller. The easiest thing to do is to increase the number of seats in government medical colleges. They have the patients – many more than they can manage. Convert this into an opportunity. Create more medical seats. Reduce the short6age of doctors in India. And since doctors and nurses have a huge demand overseas, adopt policies encouraging such manpower exports.

Instead, you now have Bangladesh teaching some 500 medical students each year. If Bangladesh can create capacities, why can’t India? Why must India finance the universities jobs and opportunities in Bangladesh?

The inability of Indian policymakers to do this, even years after dissolving the Medical Council of India (MCI), shows that reforming medical education was not uppermost on their minds. So you have a pandemic which traumatizes both the patients and the limited number of doctors. The best response of the government has been to allow ayurveds to perform operations. So why not allow government clerks to become IAS officers, or court clerks to become judges? After all, the clerks too have the knowledge about what is to be done! Such lopsided thinking will degrade even the existing standards of medical education.

The second thing investors need is quick dispute resolution. This requires immediate filling in all the vacant posts of judges and magistrates at all levels. Delayed dispute resolution is a big cost that not only pushes up the cost of doing business, but also frightens potential investors away. That is the principle reason why investors opt for international courts of arbitration, with a seat outside India. So first let domestic populations have confidence in speedy, effective dispute resolution. Foreign investors will then gain confidence. Mere assurances will not work.

Finally, let us return to the impressive figure of $ 1 trillion worth of exports by 2025. To get this level of exports, India will need FDI of over $100-200 billion year on year for the next 5-10 years. Without investments there will be no more factories or business complexes which can produce goods and services of the calibre the world wants. And investments will not come without quality people, freedom to hire competence, and significantly improved dispute resolution.

Without these, talk about boosting FDI is fanciful. Once the quantitative easing slows down world-over (including in India) expect FDI to fall, not improve.

If the government is serious about investments and exports, begin cleaning up Indian’s educational rules, its labour laws and its dispute resolution.

Else, such numbers will remain just a pipe dream.

The author is a consulting editor with FPJ.

.jpg)