Death is a serious subject. It becomes a looming grim reality when a pandemic is around. Unfortunately, India does not even know how many have died.

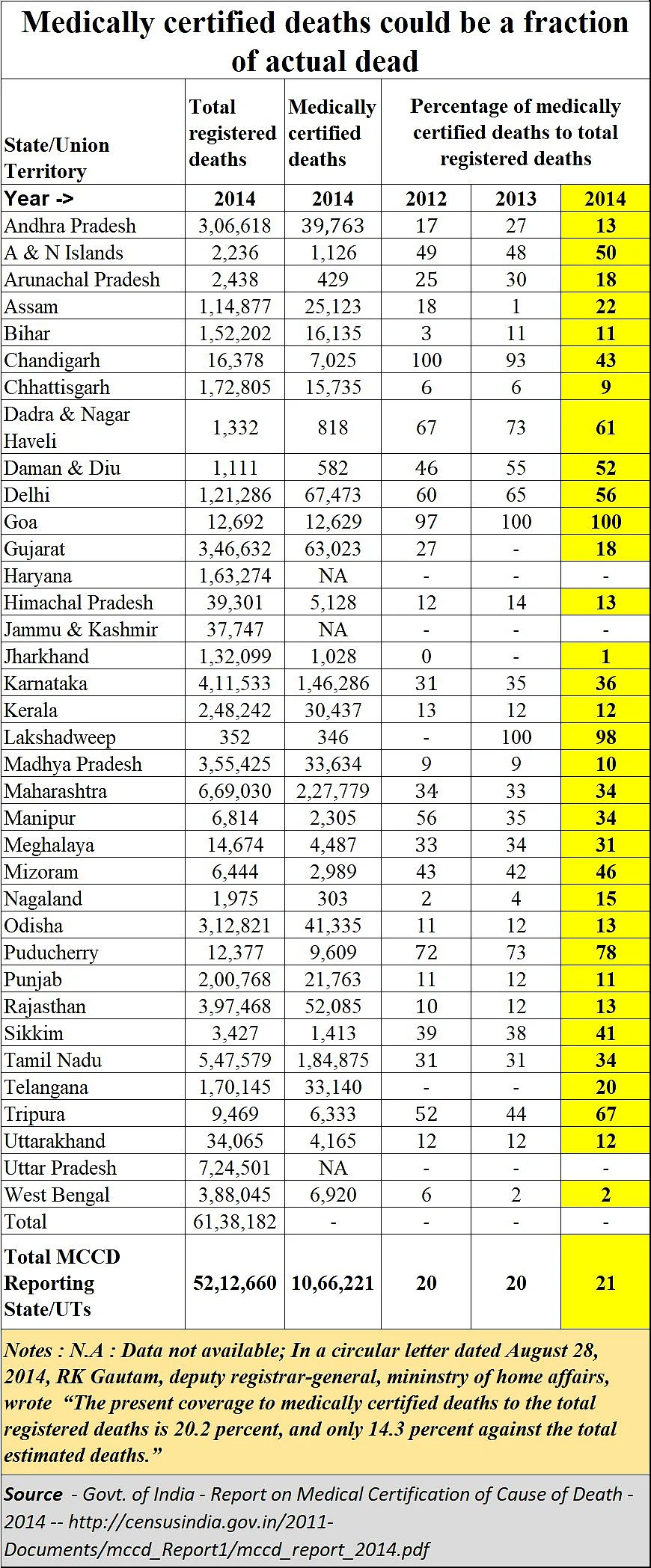

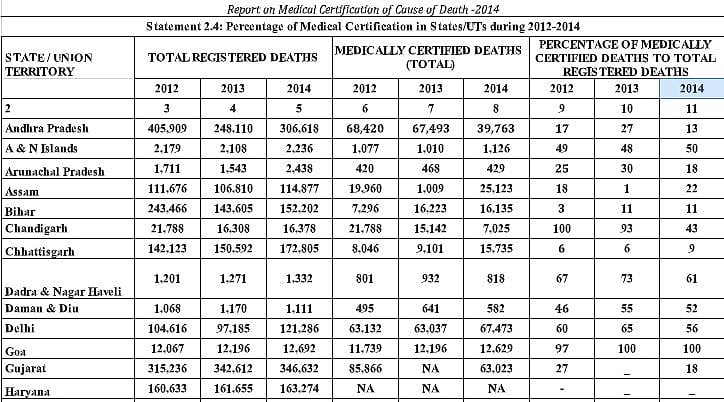

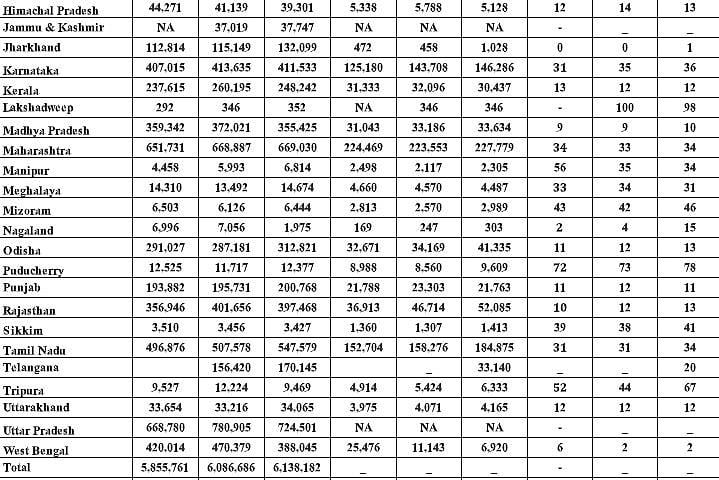

The seriousness of the problem was first driven home on 28 August, 2014, when R.K.Gautam, then Deputy Registrar General, Office of the Registrar General of India, Ministry of Home Affairs, Government of India, raised this issue . He sent out a letter-circular to the registrars of all states in India informing them that “. . . the present coverage to medically certified deaths to the total registered deaths is 20.2% and only 14.3% against the total estimated deaths.”

Gautam’s statement refers to the annual report the government used to bring out on deaths – at least till 2014. It was titled Report on Medical Certification of Cause of Death. The table reproduced alongside is an edited excerpt from the 2014 report, after which year no nationwide report is traceable.

What this report shows is alarming. It shows that only 21% of the registered deaths in the country comprised medically certified cases. In other words, almost 80% die without being medically certified about the cause of their death. The rest were just recorded as having died without a medical certificate. Moreover, if Gautam’s letter is to be believed, if unregistered deaths are considered, the share of medically certified deaths could fall to 14.3%.

Yet, if other experts are to be believed, the number of unregistered deaths could as high as 26%. Nobody really knows they died, but they are assumed to have passed away. The experts say that only 85 per cent of births and 74 per cent of deaths are registered (but not necessarily medically certified). In April, 2020, even the Kerala High Court observed that the registration of birth and death is mandatory under the Registration of Birth and Death Act, 1969.

So how does one know how many people have actually died? It is a statistical derivative, in much the same way as births – as not all births are registered. This is possibly because of two reasons. First., there is a shortage of qualified doctors in India. Second, bureaucratic apathy which has led to poor reporting structures.

When it comes to doctors, the government has done precious little to increase the number of seats in medical colleges. More private medical colleges were permitted, and many of them appear to have been mor interested in making a quick buck. Government hospitals – which are overcrowded with patients would have been ideal places to have more medical education seats. But successive governments have slept over this crying need.

Two years ago, the government appeared more keen to upgrade ayurveds, homeopaths and unanis as qualified allopaths if they appeared for a short bridge course, than in increasing medical seats. Shocking, indeed! If a bridge course would suffice, why not have a bridge course to upgrade government clerks to IAS officers? Or courtroom boys to judges? It is highly dangerous to interfere with the sanctity of any professional certification programme. Fortunately, doctors challenged this move and the matter is still pending before the courts.

Now that a pandemic has started killing people, policy makers are bemoaning the shortage of doctors. Suddenly, it is becoming clear that India spends too little on health services. At the same time, there are fears that the right numbers of the dead are not being captured yet.

The government website provides no additional details. Public access to such national reports post-2014 is just not there (though reports on some states are available).

This raises an even more serious issue. Bureaucrats will always provide a hundred reasons why information of this type is not for public consumption. But if policymakers are to be informed, there is nothing better than crowdsourcing opinions and analyses. That was the reason why the Right to Information (RTI) Act was introduced.

By preventing public access to information, policymakers allow themselves to be misled by wily bureaucrats till situations become explosive or cancerous. The best disinfectant still remains sunshine. India’s policymakers should make such reports publicly accessible as was the case before, because only then they can get additional inputs beyond what bureaucrats will reveal.

Caveat: It is possible that the percentage of medically certified deaths has increased since 2014. But it is improbable -- because the paucity of doctors is acute. Moreover, had the situation improved, the government would have advertised this. Good governance should find such apathy – even deception -- deplorable.

For now, nobody knows what the correct situation is. And that adds to the already high anxiety levels.

The author is consulting editor with FPJ