The last couple of months have witnessed a barrage of advertisements seeking to lure jewellery buyers to diamonds. They talk about how natural diamonds are the safest items of jewellery, unique and invaluable. Really?

To understand this, one needs to realise two things.

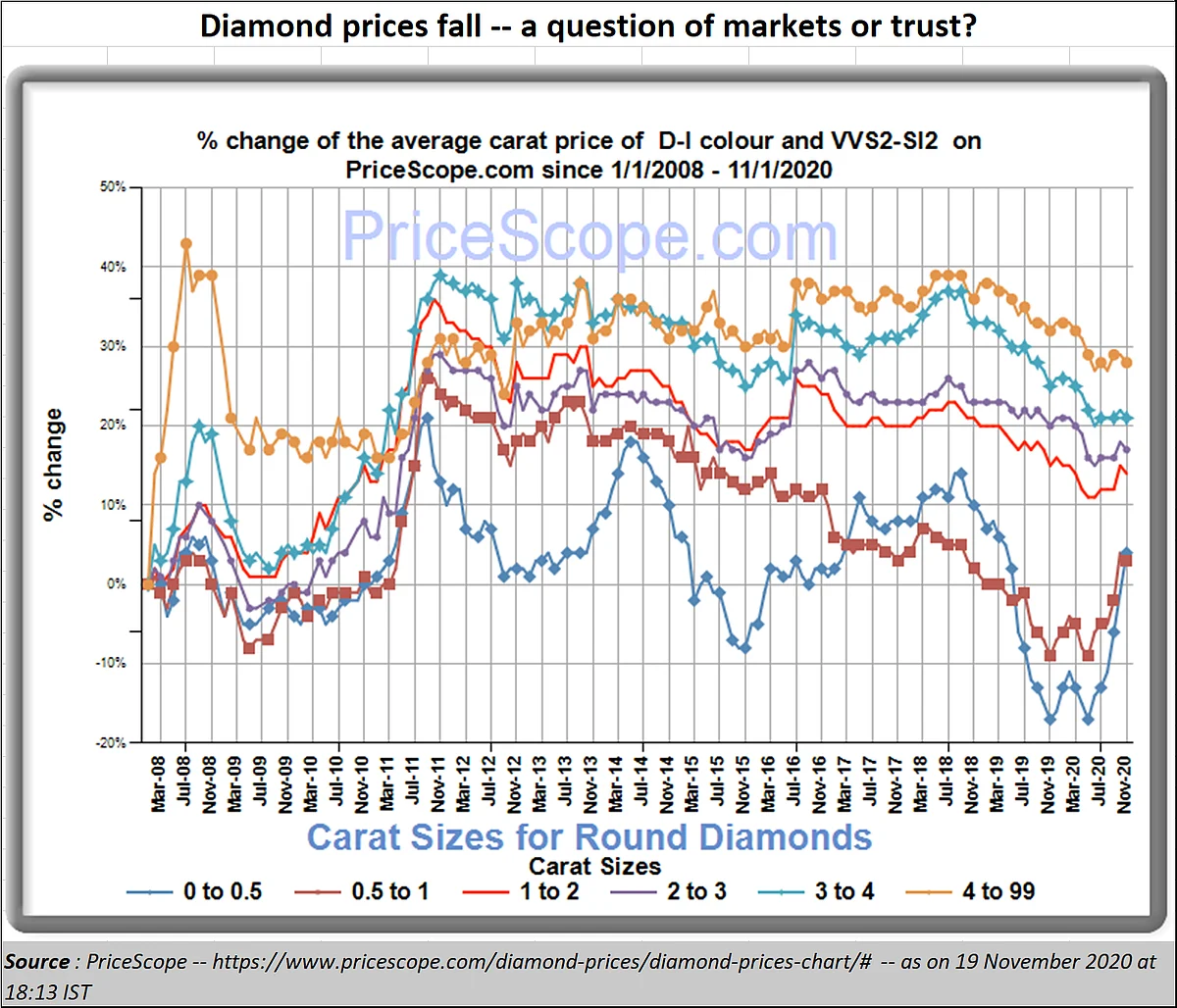

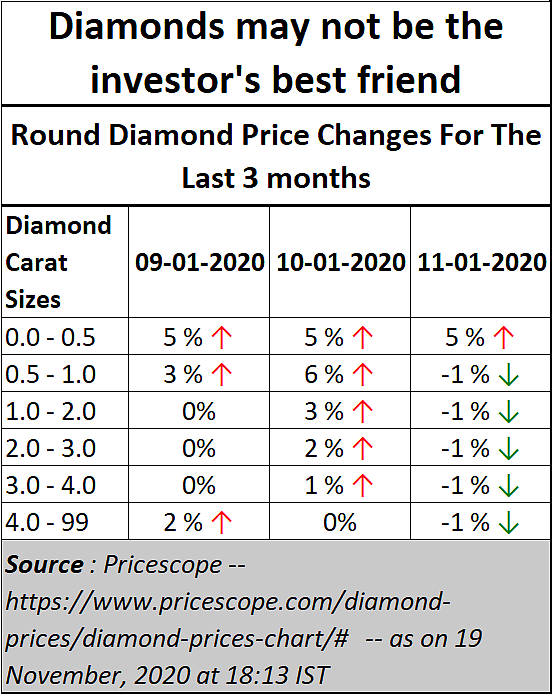

Prices of diamonds are falling (see chart below). No matter what people tell you, the lustre has gone out of this gemstone. This was captured by Bloomberg in its recent reports.

Moreover, prices are unlikely to climb back again because of several reasons.

First, De Beers—the Mecca of the diamond industry -- has actually squeezed prices out of diamond roughs to the extent possible. Note: in this article, when we refer to De Beers, we use it loosely to refer to one or all the affiliates of the De Beers conglomerate – the Diamond Trading Company (DTC), Central Selling Organisation (CSO, Diamond Producers Association (DPA), and Gemological Institute (GIA) among others. While De Beers has maintained the price of roughs it supplies to diamantaires, and through them to the cutting and polishing industry, market prices have slumped. That has caused diamantaires and the downstream industry to see their own margins squeezed. They have been hurt much more than De Beers. But more on this later.

Second, gone are the days when De Beers controlled the diamond industry. For almost 70 years, De Beers controlled almost the entire global supply of diamond roughs. Prices kept climbing year on year. That changed in the late sixties when diamond traders in Israel tried cornering roughs, using one batch of imported roughs as collateral with banks to finance another round of imports and so on. Since they were assured of ever-increasing prices, they chose to collect more roughs.

De Beers’ market intelligence told it that something was amiss – that all the roughs produced were not reaching end consumers. When they found out, they panicked.

To control prices, you need to control supply. When someone else stockpiles the products, he can control or disrupt pricing. That ‘someone’ had to be contained. De Beers asked the banks to return the collateral and demand the money back. The banks did not comply. De Beers then flooded the market with exactly those types of roughs that the banks were holding as collateral. Prices fell. Banks went bankrupt. Some diamantaires even committed suicide.

But before it caused the Israeli market to collapse, De Beers had to create another market to compensate for the lost business. So, it focused on small stones that no western diamond cutter would touch. India came into the picture. The Indian diamantaires performed so well, that they, along with De Beers, created an entire market for medium- and low-priced diamond studded jewellery. That was during the 1970s. Great days. De Beers made money. Diamond cutters and traders made money. India became the world’s largest diamond cutting and polishing centre. There was only one supplier, and that was De Beers.

By the 1980s the situation began changing. African countries wanted a good deal for themselves and wanted De Beers to buy their diamond roughs from their mines at a decent price. In some cases, De beers reached a deal, as in the case of Botswana. The join venture mining operation was called Debswana. But in other cases – Ivory Coast, Zimbabwe, Congo, and Sierra Leone—no deal could be reached. They became renegades. They had to be stopped.

De Beers could not use the “blood diamonds” route – mugging renegades or eliminating them – as it had done earlier. It had then adopted methods -- including using former heads of counter-espionage organisations -- to beat and decimate diamond traders who did not adopt the rules enforced by De Beers.

By now Russia too began selling its diamonds directly to Indians at prices lower than those of De Beers. To stop these diamonds reaching India, the world’s largest cutting and polishing centre for roughs, the trick was to persuade the Indian government to slap import duties and even ban imports from sources other than De Beers. Some diamond traders went to jail. Income tax authorities were pressed to confiscate diamond stocks.

But this tactic failed when Indian diamantaires called the biggest ever agitation against the income tax and enforcement authorities refusing to export anything till the authorities were restrained from seizing diamond stocks and thus crippling the diamond trade. By 1990, the country was desperate for foreign exchange. The diamond trade’s demands made immense business sense too. The hounds of the tax and enforcement departments were therefore asked to lay off diamond traders and exporters.

De Beers tried other ways to thwart supply of diamond roughs by these ‘renegades’. One was the Kimberly Process. The other was trying to arrive at a separate deal with the Russians. Neither worked. Instead there were accusations that De Beers was itself promoting blood diamonds, and then blaming others for such practices.

Then came the Australians with their CRA Mines which then became Argyle and then part of Rio Tinto. They arm-twisted De Beers to let them sell some of their roughs directly to the trade. Together, all these independent suppliers made De Beers lose market share in the supply of rough diamonds worldwide. Currently it controls just around 50% of the market.

Then came the next whopping blow. Lab-grown diamonds became popular because they were better in appearance and sparkle than earth-mined diamonds. They were around 30% cheaper than earth-mined diamonds. And they were without many of the flaws (often considered inauspicious by Indian diamond users) that earth-mined diamonds had. But, most importantly, the trade loved these diamonds. They allowed for higher margins than were possible from earth-mined diamonds.

Not surprisingly, even while labelling such diamonds “synthetics” and “impure” De Beers itself got into the lab-grown diamond business through its affiliate Element Six. In October this year, it announced plans of upping its production at its Oregon plant in the US. “De Beers said it has the capacity to produce 200,000 carats of polished diamonds, or 400,000 pieces of diamond jewelry, a year” stated media reports. “Those synthetic stones will be marketed under De Beers’ fashion jewellery brand, Lightbox. An exclusive collection will be sold by Blue Nile, marking the first time the 20-year-old jewelry retailer carries lab-grown diamonds”.

All through the first two decades of this century, De Beers kept increasing the price of earth-mined roughs for the trade, even though market prices could not climb further. As mentioned earlier, this left diamond cutters and polishers in a squeeze, and they saw margins shrink. Many opted for illegal methods of funding to keep the diamond trade going.

Caveat emptor

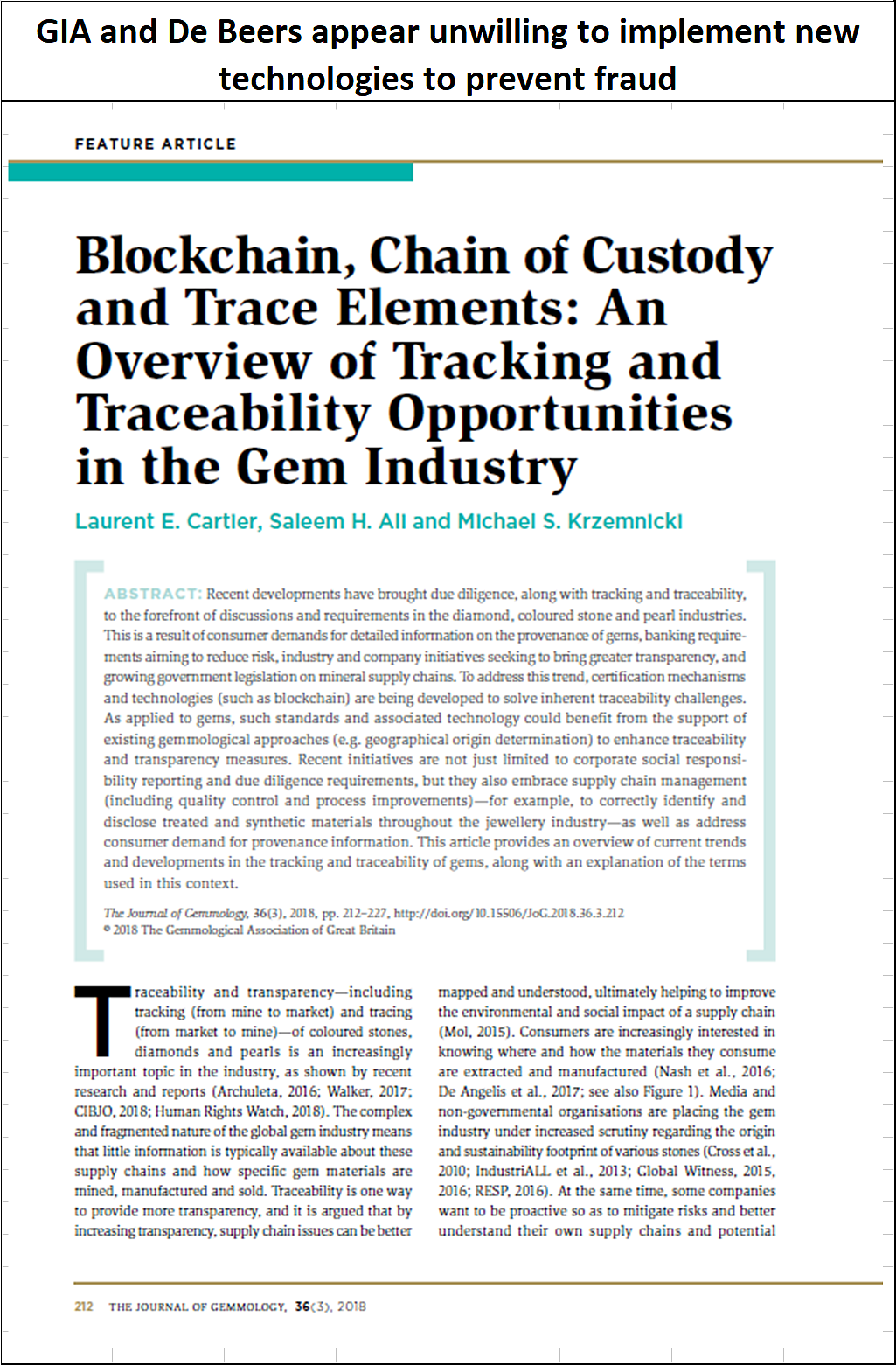

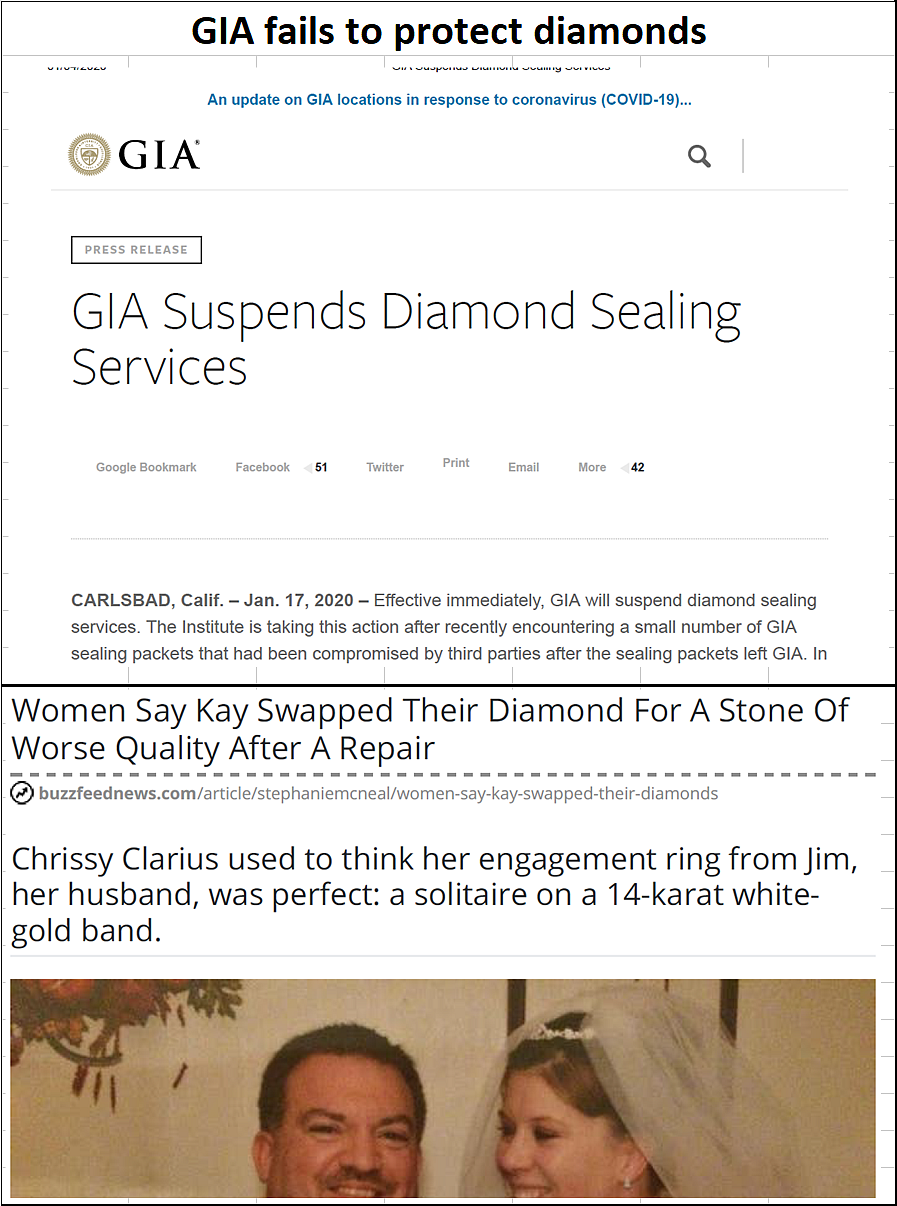

Worse, De Beers could not protect the quality of diamonds anymore. True, it had set up diamond testing centres like the GIA. But there were allegations of false reports, fabricated reports and even diamond switching. And discussions with the GIA showed that it was reluctant to guarantee prevention of switching of diamond packets given to it for testing or lodged with banks. Yes, GIA did say that it would puts its inscription on earth-mined diamonds. But even this provided ineffective as press reports pointed out. In a famous case in Belgium, where GIA accused some diamond traders of switching earth-mined and lab-grown diamonds, it was eventually found that the police department did not even have the evidence to produce in court. As incidents of switching began doing the rounds, even with diamonds sent to the laboratory for testing, or to the banks as collateral, both De Beers and GIA suspended sealing of diamond packets (see chart). That left both banks and investors on a loose limb.

Can GIA introduce new techniques to inspire confidence in the diamond trade? Difficult to say. One GIA expert merely stated: “I fear that we cannot offer any insight into the processes that other institutions may.”

As a result, new technologies that De Beers could introduce to prevent switching of diamonds, have remained unexplored. Nor has De Beers been able to work out some kind of insurance indemnifying investors who have been cheated. But GIA claims that it is a research organisation, and not one which could work out solutions for banks, financiers, or investors.

The result is that—more now than ever before -- behind each diamond purchase is the old saying-- Caveat emptor. It is the Latin term that means "let the buyer beware."

The author is consulting editor with FPJ