“April is the cruelest month, breeding

Lilacs out of the dead land, mixing

Memory and desire, stirring

Dull roots with spring rain.”

-- TS Eliot, The Wasteland

India had its own version of April as the cruelest month. The second wave of the pandemic hit the country with all its fury. It exposed past sins of commission and omission. The sheer disregard for life. The lust for power overriding common sense and caution. The refusal to exploit and strengthen strategic advantages that India enjoys. Especially when the chips are down. And the urge to play the money game even in times of death and destruction.

Some of these issues have already been covered in three earlier articles urging the government to think strategically.

One talked about the need to treat the milk and dairy sector with a lot more of respect and care than has been the case, lately. Despite this reminder, it was heartbreaking to watch the newly elected government in Assam prod the state towards banning cattle slaughter and consumption of beef. The senseless urge to treat cattle as more precious than human beings, who are dying in droves, defies logic. It does appear that some lessons aren’t learnt easily.

The government has yet to make any moves towards the promotion of CEZs (Coastal Economic Zones) which have the potential to both create jobs and bring huge FDI (foreign Direct Investments) into the country .

And it continues to drive out messengers who tell the government anything that is different from what the policymakers want to promote. Its refusal to tolerate messengers has resulted in a situation where nobody is sure about data coming from the government. Just last week, there were reports in media that even the vaccine numbers did not tally. Ditto with misleading data being presented by the government.

It was with such indirections that the government and the country stumbled from a cruel April to a crueler May. One is not very sure of how painful June will be. Even the Reserve Bank of India is worried about asset bubbles that could burst.

Bizarre developments on the agri front

In the meantime, there are worrisome reports from the farm front. On the one hand one had the tweet by All India Radio (the government-controlled radio station) that “India estimates to register record foodgrain production this year. A record 305.44 million tonnes of foodgrain production is estimated in the year 2020-21”.

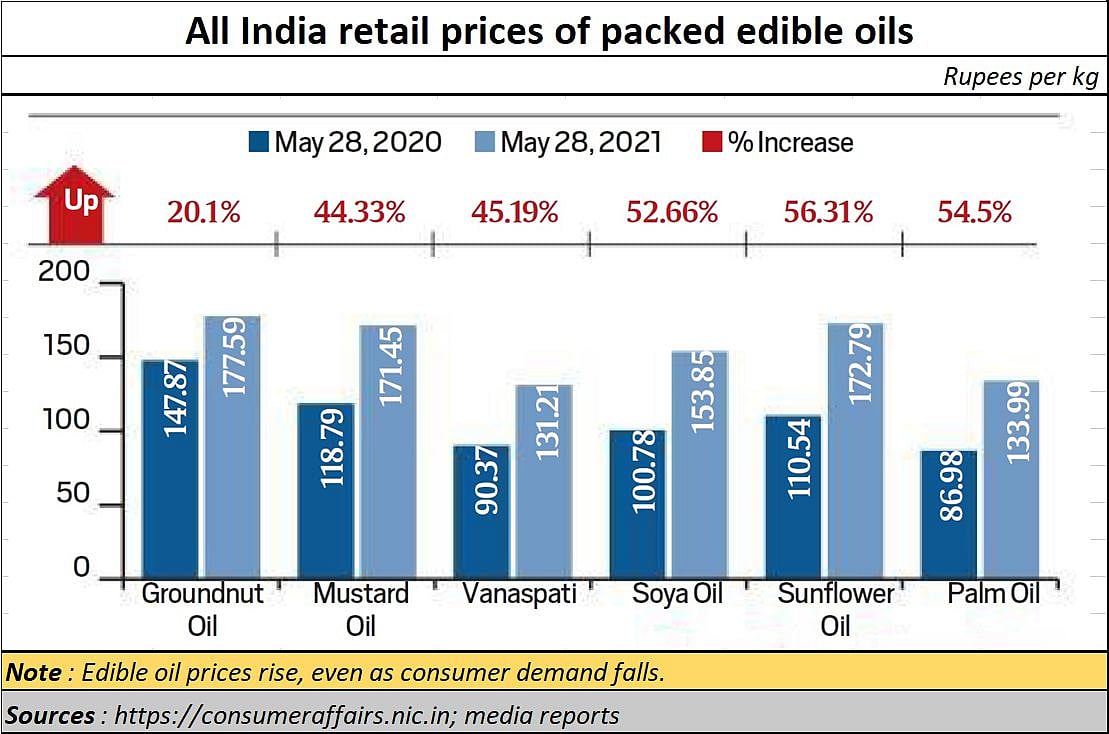

On the other hand, one also came across reports from the state civil supplies departments, that the all-India monthly average retail prices of six edible oils are at their highest in 11 years. Food Secretary Sudhanshu Pandey said that “there has been a 62% spike in the prices of domestic edible oil”. Some of the tables and charts supporting these states have disappeared from the government websites.

The monthly average retail price of mustard oil (packed) was 39% higher than in May last year. It was the cheapest in May 2010, at Rs 63.05 a kg. This was despite lower retail sales across India which declined by nearly 49% in April against the pre-pandemic levels of April 2019, according to the Retailers’ Association of India.

The India Cable reported that “HDFC Bank CEO Shashi Jagdishan struck a worrisome note when he said, ‘For the first time in so many years we probably may not have a grip on what is going to happen.’ He referred to the high probability of retail loan defaults in the second wave, and its unprecedented effect in rural markets. “

Explaining contradictions

So, you have surplus production of rice and wheat, an apparent shortage of oil seeds, a depressed consumer market in terms of demand, and runaway prices of edible oil. Normally when market demand is weak, prices ought to come down, and not go up. Yet as the meeting that the ministry of consumer affairs had with media persons , the government admitted that the prices of all the six edible oils are the highest in the last decade.

Clearly, the government hasn’t planned its agricultural strategies well at all. You have more attention being paid to rice and wheat when the combined output is less than a third of the total value of milk in the country. Even the three contentious agriculture legislations have more to do with rice and wheat and nothing to do with milk. Surely, Uttar Pradesh could have been included in the milk reform package because it is the worst exploiter of farmers? India’s GDP could have swelled by another 5-8% if all milk came under the organised milk marketing structure proposed by Verghese Kurien. Currently, barely 24% of milk is sold in the organised sector.

Promoting imports

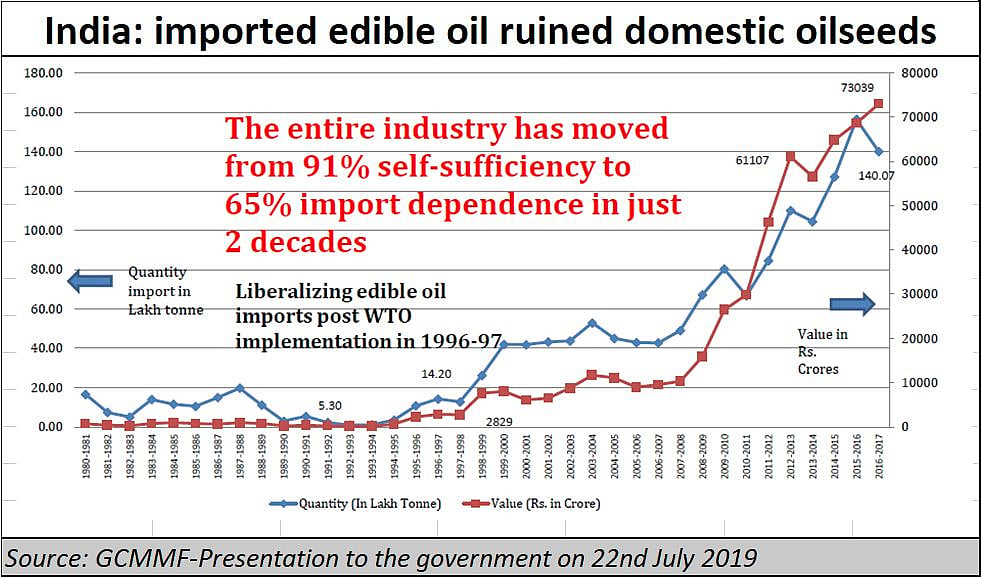

Look at another indicator. India has deliberately allowed the interests of domestic producers of oilseeds to be sacrificed so that traders of edible oils benefit. Look at the chart alongside. It shows how over the decades, successive governments have encouraged edible oil imports. That could explain why Ruchi Soya, the largest producer of soya oil and related products, went belly-up and was eventually sold to the Patanjali fold.

That is a key reason why the Dhara project of NDDB (National Dairy Development Board) failed. The Dhara project was meant to do for edible oil, what Kurien had done for milk.

Fortunately, the government appears to have woken up to the danger of depending on imports. It recently hiked the import duties on edible oil imports. As the government explains import duties on all crude and refined edible oils were raised to 35% and 45% respectively – with effect from 14 June 2018 -- while the import duty on Olive oil was increased to 40%.

In January 2020, the import duty on crude and refined palm oil was revised to 37.5% and 45% respectively. In the same month, the import policy of refined palm oil was amended from ‘free’ to ‘Restricted’ category.

But in November 2020 the import duty on crude palm oil has been revised from 37.5% to 27.5%.

There was additional policy see-sawing on the export-import front when it came to edible oils. In March 2008, the export of edible oil was banned. Then in February 2015, export of rice bran oil in bulk was permitted. In March 2017, export of groundnut oil, sesame oil, soyabean oil and maize (corn) oil was permitted. And in April 2018, export of all edible oils except mustard oil was made free without quantitative ceiling; pack size etc, till further orders.

Abetting speculation

In other words, instead of having a uniform policy which would ensure no price fall for farmers, as in the case of milk, the government itself abetted traders and speculators. Instead of helping create a farmer federation for edible oils which would allow imports when required, but also ensure sales took place only at market prices (the way NDDB does), the government fiddled with oil prices.

No wonder then, people believe that the government has spent more legislative and policy time for traders and speculators of edible oil.

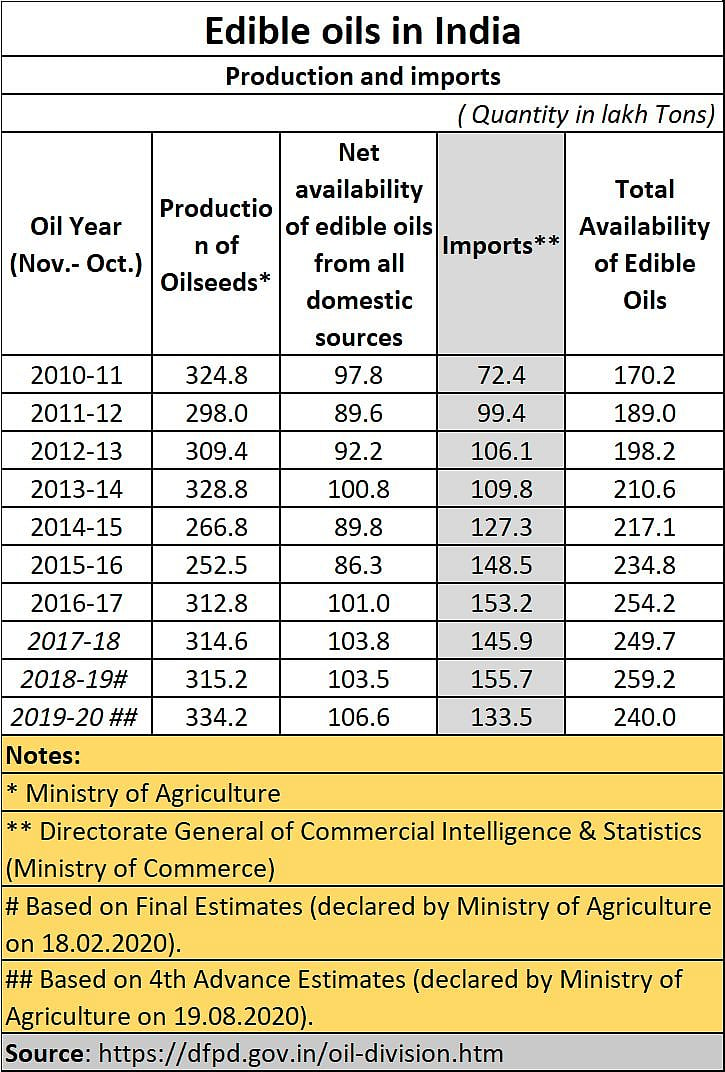

Take another indicator. The government boasts of how its measures have boosted production of oilseed since 2014. It claims that its measures have ensured that oilseed production increased impressively from about 11.3 million tonnes in 1986-87 to 33.42 million tonnes in 2019-20.

That may be true. But look at the figures alongside. Imports were allowed to double from 7.2 million tonnes to 13.3 million tonnes between 2010 and 2020. Clearly, the government has failed to put into place a policy that protects farmers and discourages speculation.

Suspicious price increase

It is in view of the above factors, that not everyone is comfortable with the way edible oil prices have soared. When demand is low, and prices go up, and the government tries showing that it is addressing the issue, there is huge cause for concern.

This is what happened with pulses as well some years ago. Domestic production was growing. Then, inexplicably, prices went up. The government saw an opportunity to import, even though everyone knew that land under pulses cultivation had increased. Prices crashed. Traders benefitted, first through imports, then by picking up domestic produce at crashed prices.

Begin hedging

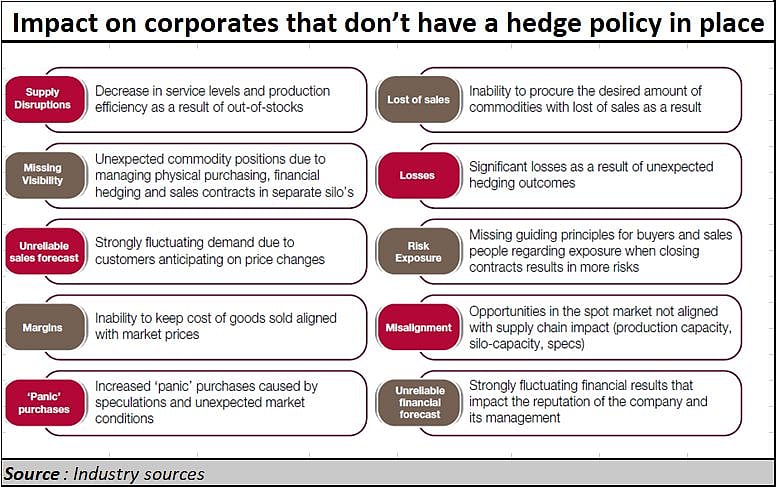

This could happen with edible oil and oilseeds as well. It is time that all oil traders and oilseed growers should hedge their positions to prevent big losses.

Commodity price risk is a financial risk. It can be addressed by a sensible policy – like the one Kurien introduced for milk – or through hedging. Since government policymaking is suspect, corporates face a challenge in dealing with volatile commodity prices as critical inputs while operating in an increasingly competitive environment. Obviously, a systematic approach to assessing risk management capabilities and hedging strategy helps in achieving risk objectives (see chart).

Globally the food and beverage sector has the largest share in price risk management vis a vis other sectors like chemicals & life sciences, metals etc.

A breath-taking rally in soybean from below Rs. 4,000 per quintal in October to nearly Rs. 8,000 in April has stunned stalwarts in the agricultural marketing sector. But it was not an accident. Many factors -- such as sharp fall in the global supply of this largest grown oilseed, followed by increase in consumption of soyabean derivatives in China and some nations in the West – triggered the global rally.

Discourage rice and wheat

In fact, the way wheat and rice production and support prices have been allowed to soar is extremely worrisome. We produce more than we require. And at prices that make export a loss-making proposition for India. Much of it goes waste, thus destroying evidence of higher prices being paid out for inferior quality grain.

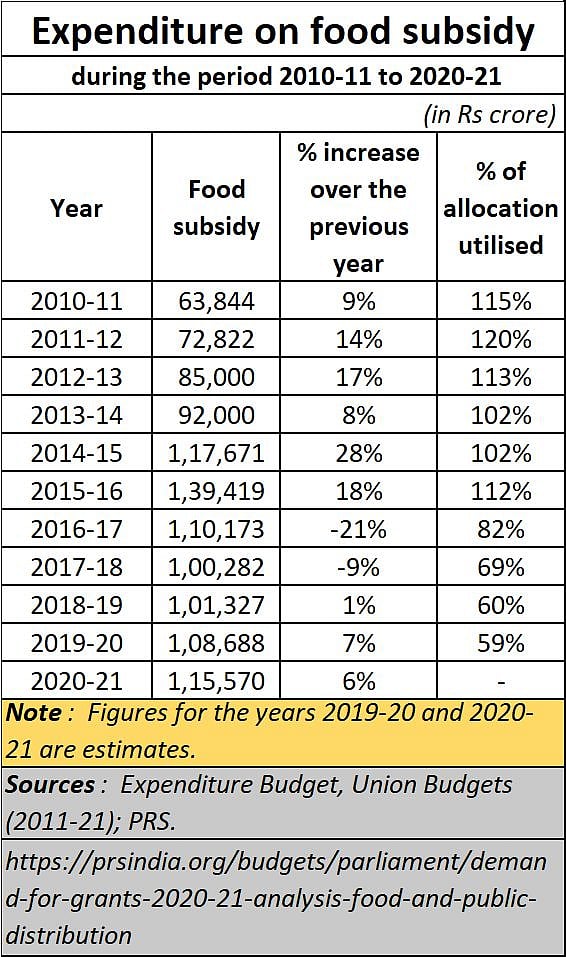

India’s agricultural policies should wean farmers away from these two grains to reduce the huge food subsidies that are being paid out year after year (see chart). Except for two years, 2015-16 and 2016-17, when the government did try to reduce food subsidy (though marginally), it has been allowed to soar again. Subsidies are politically appealing, though they are economically disastrous. As with Covid, politicians love votes more than the economy or human lives.

With the food subsidy drain on one side, and the huge damage to the economy on the other, thanks to inept handling of the pandemic, any further loss to farmers because of oil imports by the trade could wreck agricultural fortunes. It could set back farmer confidence in growing oilseeds for the next few years.

If the government is serious about agricultural reform, it must immediately revive the Dhara movement that was initiated by Kurien. It must strengthen farmer producer organisation (FPO) federations for each type of crop. It must move away from fiddling with agricultural prices and with policies relating to exports and imports.

Equally important, it must move away from the regime of subsidies which promote the inefficient and hurt efficiency. Let the FPO Federations decide if import of agricultural commodities is required. Just pass suitable laws that sale of such imported goods will not be prices less than prevailing prices, and let these federations learn to finance themselves the way NDDB used do under Kurien. This way, the power of politicians to fiddle with prices gets muzzled, and the risk of going against World Trade Organisation (WTO) rules is minimized. Agriculture requires both.

Subsidies destroy industries, especially farming communities. Tinkering with import and export policies do tremendous damage to the national fabric. The government should now focus on promoting producers and not speculators.

The author is consulting editor with FPJ