“For God's sake, let us sit upon the ground

And tell sad stories of the death of kings ...”

- Richard II, William Shakespeare

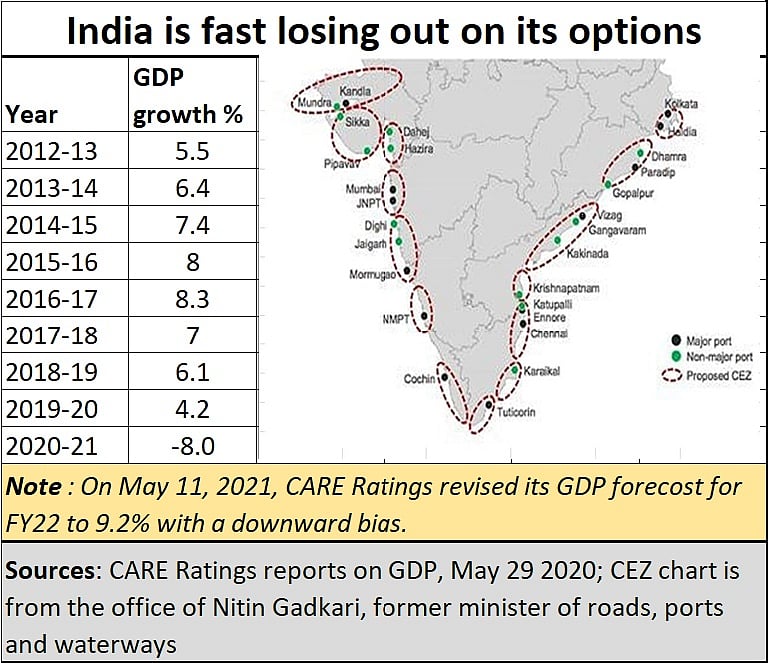

Could the CEZ (coastal economic zone) concept be India’s hope for salvation. Most emphatically, yes.

India’s ratings are collapsing. It now has the lowest investment grade rating with a negative outlook from all three major global agencies — S&P, Fitch and Moody’s. That will make raising funds extremely difficult, just when India needs investments desperately. Another downgrade would push the rating below investment grade.

We spoke of the CEZ in December 2016. We need to talk about it again.

But first a backgrounder.

Three major disappointments

Hindsight can make people wise, but only if they seek answers. At the moment, few are sure about how to view the past. But for people like this author, India had three major milestones when the tide could have turned, and the country could have been a major player among the best in the world.

The first was when a demagogue – Indira Gandhi -- was defeated at the hustings. Jayaprakash Narayan (JP) became the icon around whom everyone rallied. The youth was ecstatic. Change was in the air. But JP fell ill, and let others rule the country. He died shortly thereafter. The new government literally disintegrated. Nobody was strong enough to hold together disparate views and allegiances.

The second was when Narasimha Rao ushered in liberalisation. Expectations ran high. India’s fortunes rose. But the Congress party pulled the rug from under Rao’s feet. And when he died, he wasn’t even given a decent cremation. But hopes were not dashed. The BJP came to power supported by other parties, with Atal Bihari Vajpayee at the helm. Briefly, it looked as if India could shine bright. But somehow, he was pulled down in the next elections (some believe that the RSS chose not to support him because he refused to accept any of its outlandish ideologies). UPA-1 led by the Congress, rode the crest, and the economy did fairly well. But UPA II was a disaster. The stench of corruption filled the air. Bank money was misused (a malaise even the current government has not cared to prevent.

Then came Narendra Modi. His track record as Gujarat’s chief minister made him the most promising candidate to lead the country. Once more aspirations ran high. He spoke the right words – less government, more governance. Transparency. Pulling everyone along with him. Subsequent developments made a mockery of such pronouncements. Unilateralism and centralisation meant little information was shared, and the government’s face began intruding everywhere. Corruption reared its head again. Not surprisingly, the country’s fortunes began sagging. The Covid pandemic accentuated the flaws and cracks.

At each of these turning points, history was made, and unmade. Hopes were raised and dashed. India stumbled each time. But it learnt to pick up the pieces and hobble along.

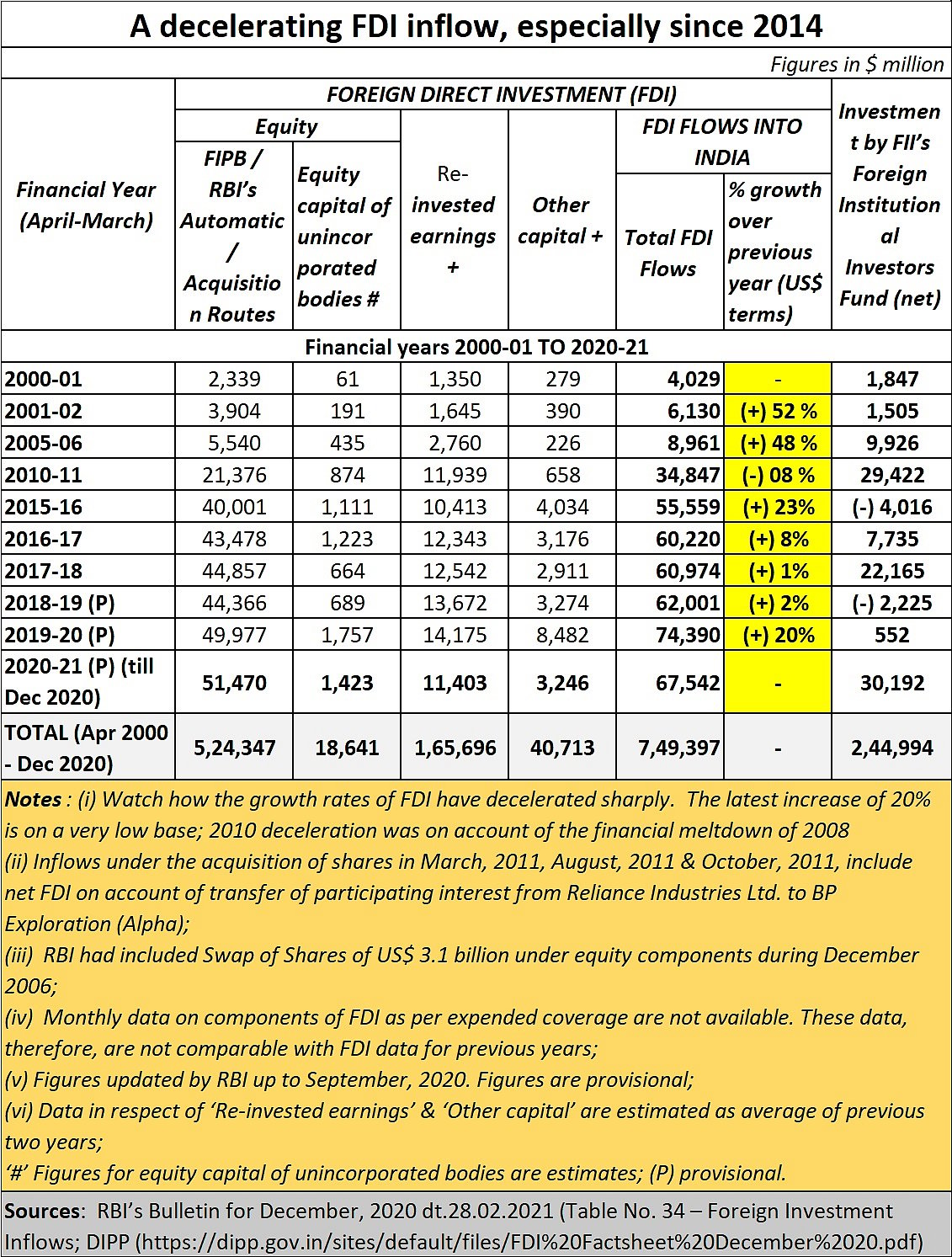

This time, however, there is a fear that if India stumbles, it may not be able to regain its feet and its bearings. It will need props – of vigilantes, or a foreign country. Its GDP growth rate has been plummeting. And while FY22 may end with a 9.2% GDP, it is possible that actual GDP will still be lower than the GDP of FY20 (see chart).

FDI needed urgently

If India must survive, it needs to ensure purchasing power in rural India does not fall. It must revive the cattle trade. Else the contagion will spread, not merely because of the Covid virus.

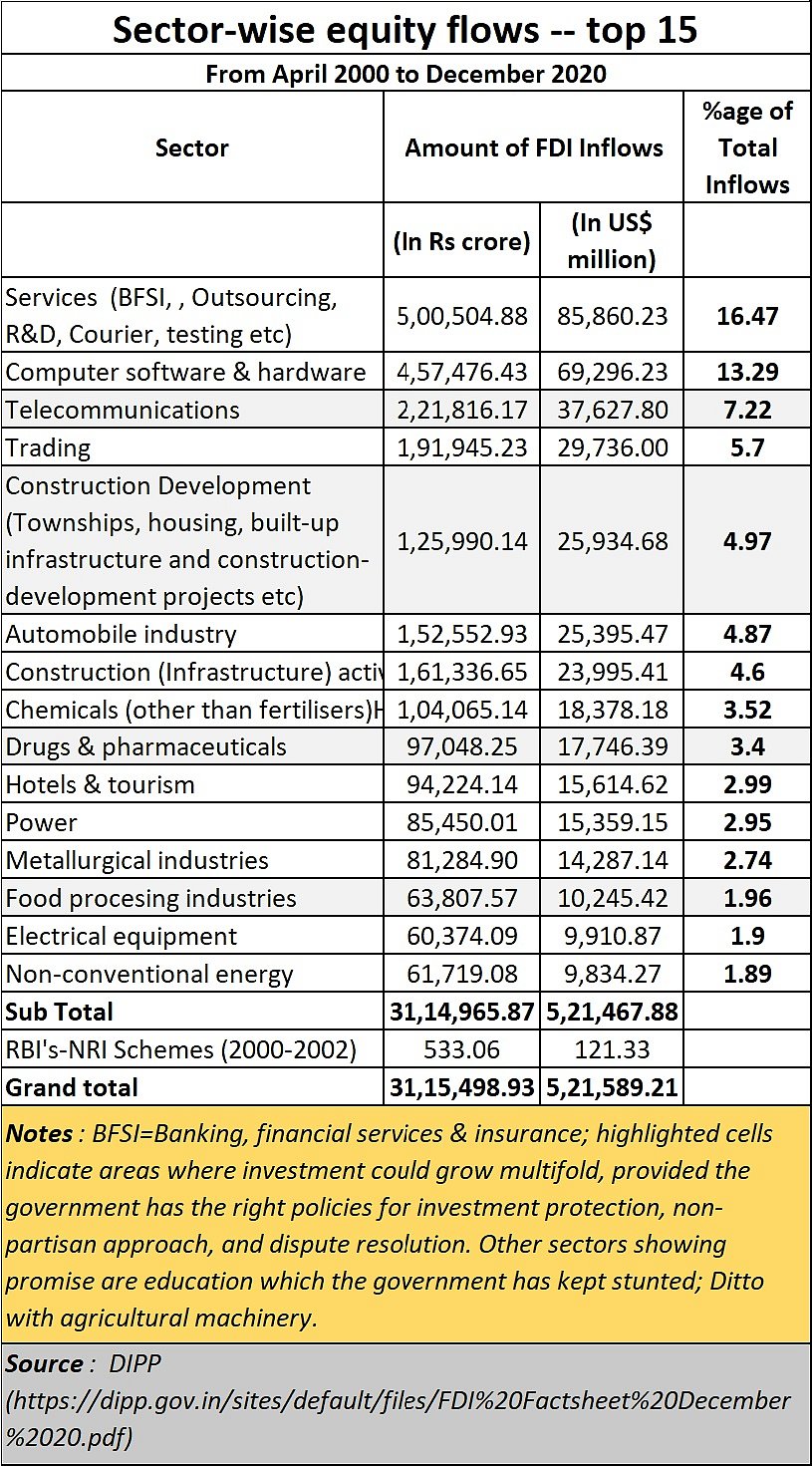

It needs FDI (foreign direct investments to revive the industry and service sectors, which can bring about rapid growth and wealth generation. But FDI inflow into India has been decelerating.

As against healthier growth rates of the past three decades (except for 2010-11 on account of the global financial meltdown of 2008), FDI inflows have dropped to single digits. They increased again a bit in 2019-20, but on a considerably smaller base.

So, why did FDI growth slump? Three reasons.

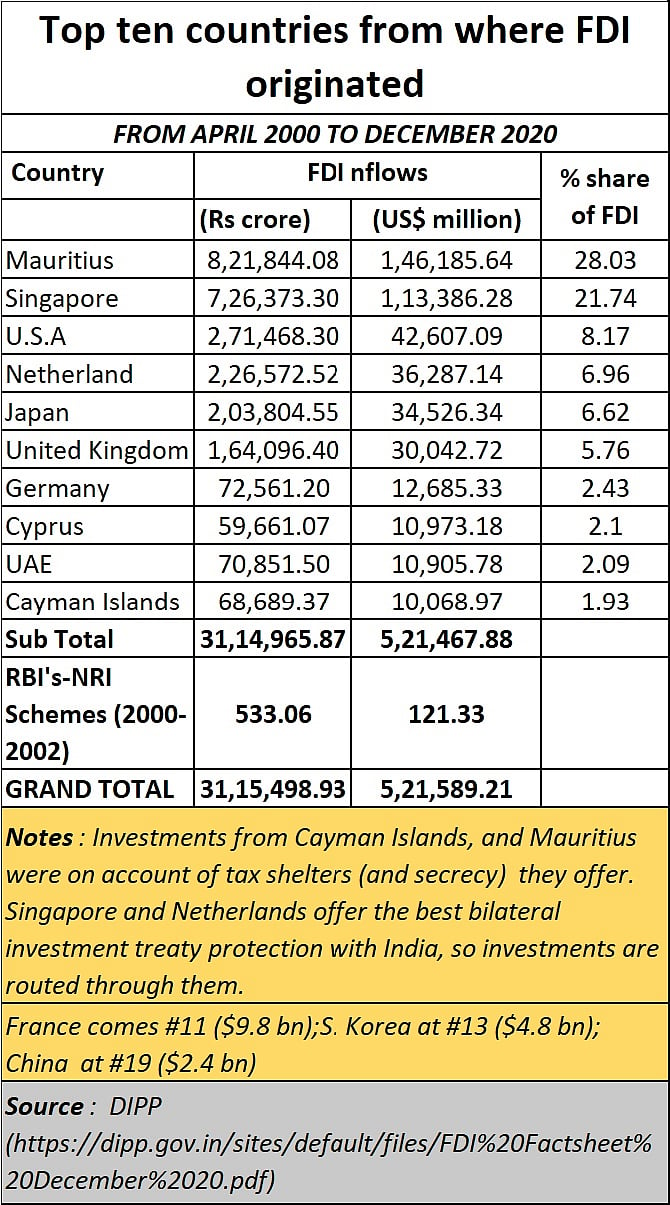

The first was the restraint the government put on foreign investors. They were prevented from approaching international arbitration tribunals for speedy redressal of disputes.

The second was the cancellation of almost all the bilateral investment treaties (BITs) the government had with investor countries. Without recourse to international arbitration, and without the guarantee of investment protection, investors became increasingly nervous. Today, Singapore and the Netherlands are two countries with which India still has BIT. Highly placed sources tell us that the government tried exerting pressure on both countries to prematurely terminate their BITs. Both refused. Thus, so long as the BITs are valid, investors will choose to invest into India through these countries. That way their investments enjoy protection under the BITs – if the agreements are signed before the BITs lapse. Not surprisingly, some of the largest investments come through Singapore and the Netherlands. Mauritius was a traditional tax haven with a BIT protection. Not any longer.

Arrogance reduces allure

The third reason is the government’s arrogance. When it scrapped the BIYs, it offered the countries a modified BIT which had the clause stating that they would not approach an international tribunal, till they had exhausted existing legal remedies in India. Nobody signed this agreement except Cambodia and Belarus. These are countries with which India has hardly any business deals.

It is this arrogance that made India refuse to accept any international arbitration awards which have gone against it. It refuses to accept the Vodafone award, and is appealing against it. Ditto with the Vedanta award -- the latter has filed for attachment of assets (Air India) to recover the amounts owed to it. It refuses to accept the Devas Multimedia award. It lost the first appeal, then lost the second appeal as well and was slapped with a higher penalty. Now, possibly to wriggle out of the Devas award, it has slapped criminal charges against the promoters of Devas, in the hope that the criminal charges could be used as a justification for not meeting damages payable. That is dishonesty. That too is being challenged in international courts.

That arrogance took yet another form. When countries opposed India, it immediately stopped banned to its markets. It was confident that countries would be so desperate to tap into India’s market, that they would overlook other flaws like investment protection. That has not worked out as well as was thought.

The Covid pandemic accelerated the trends of deceleration that were already evident. Suddenly, India discovered that its middle class too had shrunk. A shrunken market reduced India’s appeal. Citibank has opted to walk out. So has General Motors. Ditto with other auto companies.

Meanwhile, unemployment has also risen sharply. Capital had rapidly shunning India. Its government is reduced to wooing the UK which already has a record of swindling India both pre-Independence and post-Independence in 1984 with its Westland helicopters. It was a ‘gift’ that turned out more expensive than buying such aircraft. Even recently, it tried to be extortionate in its visa fees.

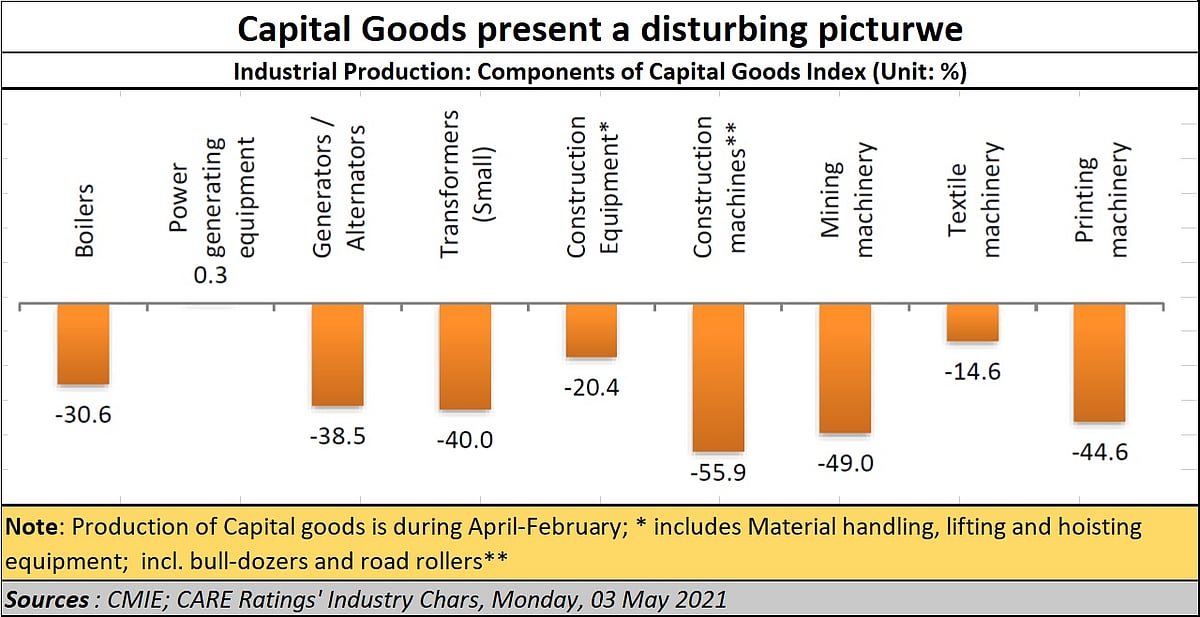

Almost all indicators relating to capital goods have also began registering painful declines.

So, what does India do?

The one major trump card India could use is to announce that country partners can now take charge of one or more CEZs (coastal economic zones). These industrial zones – almost as large as a city – ought to be given away to a partner-country-investor.

A CEZ would thus be given the status of a protected territory under Section 234Q of the Indian Constitution. It would have the right to international arbitration, and all the provisions of the BITs that the government had earlier cancelled. It would combine the benefits that Indian ports offer to port terminals given out to least to foreign companies for concession periods of 25-50 years, and those that centres like NOIDA (near Delhi) enjoy. Remember, NOIDA has survived even the worst police and administrative excesses that Uttar Pradesh has witnessed. It is a joint agreement between the NOIDA authority, the central government, and the state government. Thus even while UP burns, NOIDA has continued to attract investments.

Since such a zone would be free from the police raj that the rest of the country is subject to, has recourse to alternative dispute resolution mechanisms, and can export and even sell to the domestic market, it almost eliminates all the problems talked about above.

Our discussions with two countries – Germany and Japan – suggest that they would be willing to take up major investments in CEZs if the concession period were for 60 years. This is because building a new city, its social infrastructure and its residential and recreation areas will take at least 5-10 years. But since, such a city would not require any municipal clearances, except a broad principle of adhering to broad city guidelines, the construction should move along at a rapid pace, import of machinery and key people made easier. It could also enjoy revenues (to be shared with the state government) from leasing out development and advertising rights to its investors.

Within a CEZ even hotels could still continue business, even though this sector will see a collapse in FDI for the next few years. Other sectors that could see a huge surge in investments within the CEZ would be drugs & pharmaceuticals, food processing industries, BFSI enterprises, electric vehicles, and telecommunications. Since the country has been crying out for investments in education, the CEZ could attract huge investments in education, medicare services even hospital tourism. The potential is mind-boggling. And since a CEZ involves building a township, expect this sector to boom as well

This would immediately allow India to get a surge in investment, and the investor to focus on managing his investments rather than government procedures. You just need one CEZ to trigger a series of such investments in other CEZs. India will then not require the crutch of foreign nations which command India how to wag its tail.

CEZs could create jobs, boost exports, and give India the sorely needed breathing space it needs to set right the rest of its domestic policies.

Without such large dollops of investment, India could sink lower to the point when Africa becomes more interesting as an investment destination for global investors.

Of course, the government will have to swallow its pride. But that is better than losing one’s face, and then losing everything. The loss of pride is more inevitable in the second scenario.

India needs humility, sagacity, and love for the country (not just in slogans, but in action) to push the CEZ concept. The time is right. The need is immense. The opportunities even greater.

The author is consulting editor with FPJ