Another celebrity couple—Priyanka Chopra and Nick Jonas—had a baby using a surrogate; somewhere at the bottom of the report was the information that it was the woman’s fifth surrogacy. Which probably means, the woman was not carrying someone else’s baby out of the goodness of her heart, or for a fat fee, she was a professional ‘womb for hire.’

Like in the west, in India too, celebrities married (Shah Rukh Khan, Aamir Khan, Sunny Leone, Shilpa Shetty, Preity Zinta, Lisa Ray, Shreyas Talpade) and single (Karan Johar, Ektaa Kapoor, Tusshar Kapoor) have opted for parenthood the surrogacy way. They could have adopted, but to the Indian ‘apna khoon’ mindset, genes matter.

There are aspects of surrogacy that are disturbing, mainly the commercialisation of the process. It divests the woman of the physical, emotional and social sides of motherhood, and reduces her to one useful body part; particularly ironic in a country like India, where the mother is worshipped—at least theoretically.

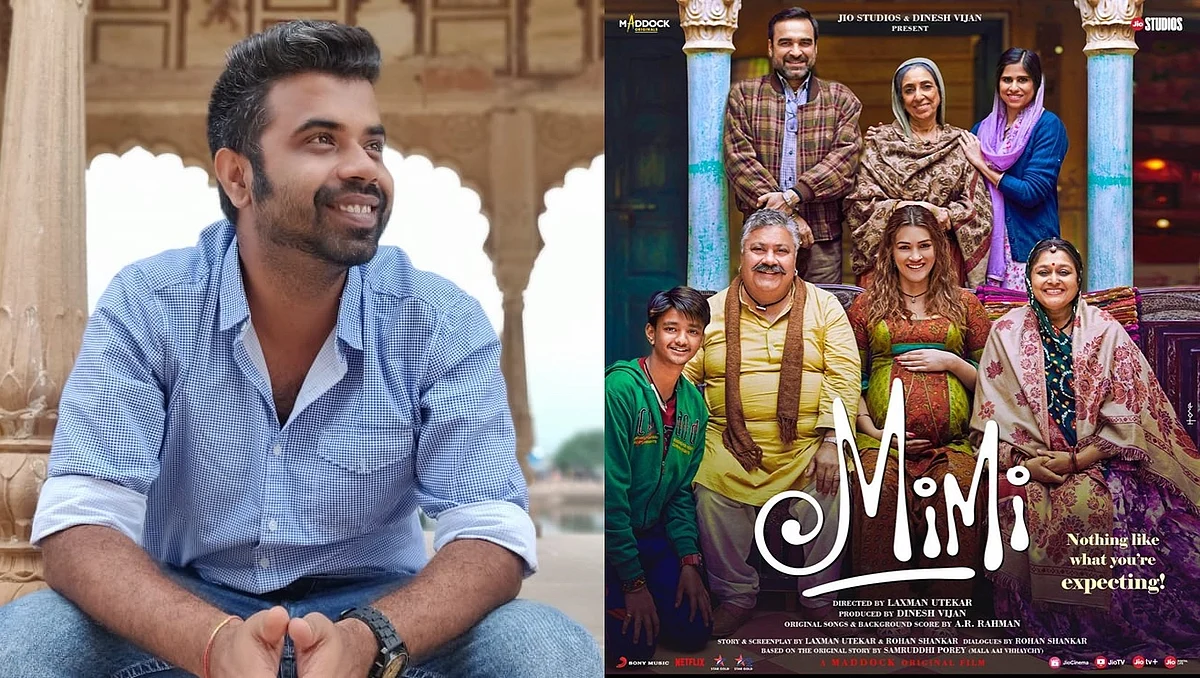

All feature films made about surrogacy, from the relatively new ‘Mimi’, to older films like ‘Doosri Dulhan’, ‘Chori Chori Chupke Chupke’ and ‘Filhaal’, focused on the awakening of the maternal instinct in the woman carrying another’s baby.

In ‘Mimi’ (adapted from a Marathi original, ‘Mala Aai Vhaychay’), when a foetal abnormality is detected, the American couple that had hired an Indian woman to be a surrogate, simply abandon her. Later, when they discover the baby was born normal, they return to claim the child.

However, what if the baby had been born with severe disabilities? Who would have taken the responsibility of raising the child? The pro-surrogacy opinion is that women should be free to choose if they want to monetise their wombs, but in reality, there is always the risk of exploitation.

In India, poor rural women, who are usually hired by middlemen to be surrogates for the rich—often Western— women would almost never have any control over the contracts their husbands enter into with touts, and none over the money received.

There have been cases, in which a husband took the money and left the wife, for bearing another man’s baby. Besides, for this class of underprivileged women, who are usually recruited for surrogacy, nobody cares much about health insurance, delivery and post-birth complications, or the long-term effects of repeated pregnancies. If she dies, it is easy to sweep the matter under the carpet.

In a piece in opencanada.org, Natasha Comeau, wrote, “The business of commercialised surrogacy in India began in 2002 and the country quickly became one of the top surrogacy destinations for foreign couples. This move coincided with many countries, including Canada, banning commercial surrogacy and moving to highly regulated altruistic systems. Because India has a high proportion of skilled doctors and a large population of young women eager to make money that might otherwise be beyond their reach.” She also quotes Sally Rhoads-Heinrich, a surrogacy consultant as saying, “India had the perfect opportunity to make an amazing surrogacy system,” but she also thinks that the involvement of exploitative third-party businesses removed the possibility for relationships between surrogates and parents, and therefore, India missed an opportunity to bring humanity into such a personal process.

The altruistic model means that if a couple unable to have children, or a gay couple want to have a child using a surrogate, then they can have a friend or relative bear the child, without money changing hands.

There have been reports of mothers carrying their daughter’s child. There have been dozens of feature films and documentaries made on the subject of surrogacy. One of the earliest, was ‘Google Baby’ (2009) by Zippi Brand Frank, in which she examined the surrogacy industry across three continents.

An Israeli entrepreneur, Doron, who got a baby through a surrogate in the US and found the procedure very costly, decided to start a business and outsourced the baby-making to India. In the West, just legal fees and insurance would make the procedure prohibitively expensive, hence the hiring of Indian wombs.

In 2010, Rebecca Haimowitz and Vaishali Sinha directed ‘Made in India’, about the surrogacy boom in India. The synopsis of the film states, “In San Antonio, TX, Lisa and Brian Switzer sell their house and risk all their savings on a Medical Tourism company. This company promised them an affordable solution after 7 years of infertility. Across the world in Mumbai, India, Aasia Khan puts on a burka - not for religious reasons - but to hide her identity from neighbors as she enters a fertility clinic to be implanted with this American couple's embryos. These are the scenes that unfold as we watch East meet West in suburbs and shantytowns, in test tubes and Petri dishes, in surrogates and infertile couples....”

There are moral, legal and ethical issues involved, which is why many countries have simply banned commercial surrogacy, or at least regulated it. India’s record in the matter of women’s rights is not that great, but transactional surrogacy was banned in 2015, and perhaps taking into account the criticism of the commodification of women, two acts were recently passed in Parliament — the Assisted Reproductive Technology (Regulation) Bill and the Surrogacy (Regulation) Bill.

Fines and jail terms are laid out for medical practitioners and couples who seek commercial surrogacy, but implementing laws is always tough when so much of this activity can so easily be conducted in secrecy, and the guidelines of the law easily circumvented. So couples—hetero or same sex—will have ticked a long list of eligibility criteria, while celebrities flaunt their designer babies, and some faceless woman goes through the hassles of pregnancy and child birth.

‘Breeders: A Subclass Of Women’ (2014) by Jennifer Lahl and Matthew Eppinette, takes a very critical look at the issue, following the stories of four surrogate mothers, and a young woman who was born by this method. A surrogate mother, Tanya Prashad, who gave birth to a girl, says she regretted it right away.

“When she was right there in my arms, all those little pieces of paper that we signed kind of just fell away. I never for a second thought about what was right for her and what she deserved.” She fought to get joint custody of the child, and one cannot imagine the emotional problems both sides must have gone through, not to mention the hapless kid.

Lahl made documentaries, ‘Eggsploitation’, about egg donation, and ‘Anonymous Father’s Day’, on sperm donation. She believes the multi-billion-dollar global reproductive industry conceals the health risks for prospective surrogates and equates it to selling organs. “If you want to be a kidney donor, we say that’s wonderful, but you are not allowed to be paid… because what happens when commerce enters in is people will make decisions that are not in the best interest for their health,” she says, “Women are not breeders.

Children are not products and commodities. Women are not easy-bake ovens baking cupcakes for nice, other people.” Jessica Kern always wondered why she looked nothing like her mother, and when she discovered the truth about her birth, tracked down her biological mother and learnt that she had been paid $10,000 to give birth to her.

“I'm not fond of the fact that I’m born through a paycheck,” she says. As technology develops, it gets closer to sci-fi—writers have imagined dystopian scenarios in which women are bred for the use of their wombs (think Margaret Atwood’s ‘The Handmaid’s Tale’), and a terrifying tale, ‘In The Barn’ by Piers Anthony, that appeared in the classic anthology Again, ‘Dangerous Visions’, in which women are reared as milch cows… because once a line is crossed, it is usually too late to call for wisdom or caution.

The writer is a Mumbai-based columnist, critic and author